Faces of Wagner

IStories looked into the life stories of the convicted criminals who died in Ukraine and were recruited by Russia’s infamous paramilitary organization Wagner PMC, talked to the victims of their crimes, relatives and friends

“We need your criminal talents,” says Yevgeny Prigozhin, addressing a sea of Russian convicts dressed all in black. “Our ideal candidate,” he continues, “is 30-45 years old. Strong, confident, hardy. Ideally, he’s served at least fifteen years. Ideally, he’ll have another fifteen years, or more, ahead of him. He’s in for multiple murders, severe assaults, robberies. If he’s fucked up some official or cop, even better.”

His audience laughs. Prigozhin is the swaggering leader of Russia’s best-known paramilitary organization, Wagner Group. In this video, filmed in a Russian prison this February, he’s describing the type of men he’s been recruiting to fight the group’s battles in Ukraine.

More than 50,000 prisoners have joined Wagner Group since Russia’s 2022 invasion, according to the non-profit advocacy organization Russia Behind Bars.

Many have deserted or been killed or captured, the Wagner force seriously depleted in Russia’s grinding battle for Bakhmut and other towns in eastern Ukraine.

Though hiring mercenaries is technically illegal in Russia, that hasn’t stopped the state from turning them into heroes. They receive posthumous medals and honors, feature in propaganda films, and are buried with military honors.

But who are these “ideal candidates?” And what leads them to join a nearly hopeless fight?

IStories looked into the life stories of three former prisoners who signed up to fight for Wagner in Ukraine, and died there. None lasted on the battlefield for longer than a few months.

Little is known about what they experienced in the war or how they died. But conversations with their friends, their families, and even their victims, give some insight into their lives — often bleak and blighted by alcoholism and senseless violence long before they went off to the battlefield.

This article was translated and edited by OCCRP.

“The Truth Seeker”

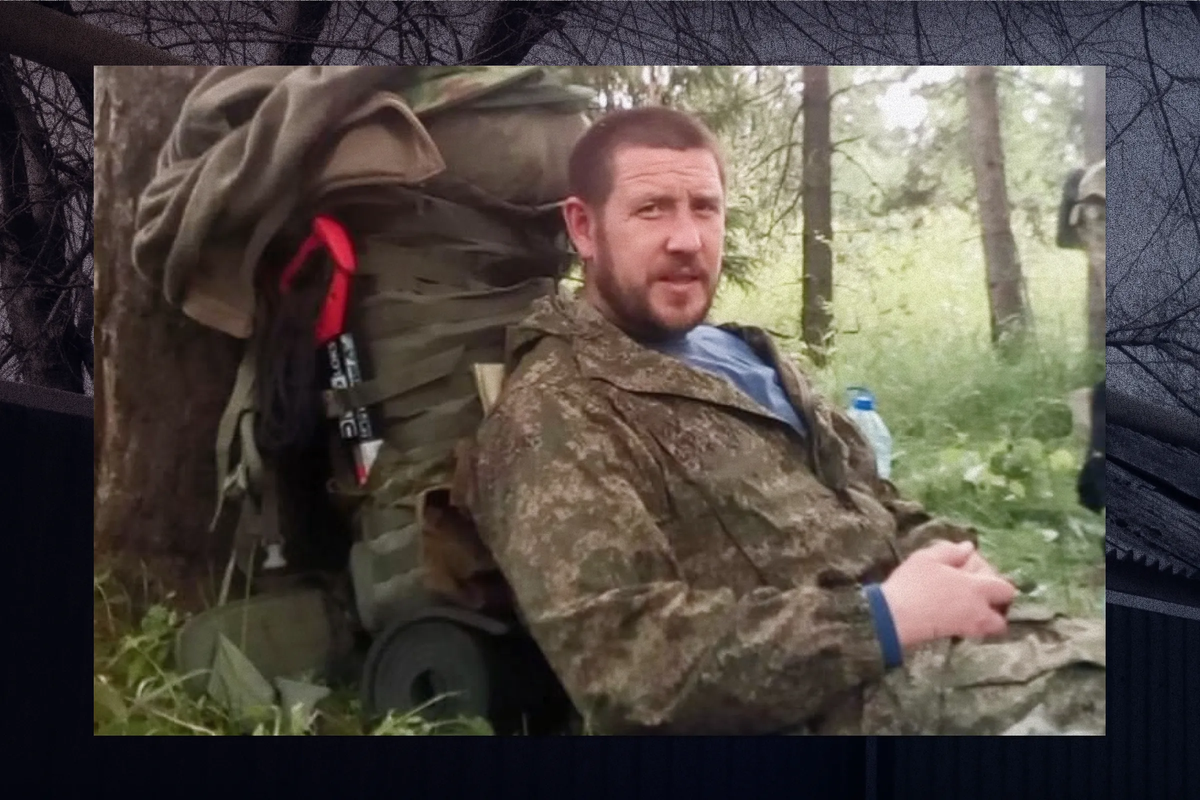

Alexander Sitavichus fought in Ukraine for just two months before being killed. Today, the former salesman of agricultural products and father of four is back home in a Russian village — buried in the same cemetery as the three people he was jailed for murdering.

The targets of his drunken bout of racist violence were fellow residents of Ladozhskaya, the rural Cossack settlement in southwestern Russia that Sitavichus called home.

Stretching along a bank of the meandering Kuban river, several hours’ drive from occupied Crimea, his hometown is not rich in entertainment options. One of these is Ogonyok, a modest bar and restaurant where, on the last day of 2017, Sitavichus’s life changed forever.

By then he was already a veteran of the war against Ukraine, having traveled there in 2014 as Russia sought to break the country’s eastern regions away from Ukraine.

“Sasha is this kind of guy who has a sharpened sense of justice,” recalls his friend Alexei Gaivoronsky. “He went to the Donbass right away in 2014, to save the ‘Russian world’ [a concept of social totality associated with Russian culture, history and language]. You know, all classically Russian people, they’re always driven by their emotions, they never think with facts.”

“That was his character,” says Sitavichus’s widow, Oksana. “He had to be everywhere. He was ideological, let’s say. He was always fighting for the just cause.”

By 2017, Sitavichus had returned to his hometown. On that winter night at the very end of the year, he was getting drunk with an old friend from the war.

Then, for reasons that are unclear, the two men got into a fight with several others. Their opponents, visible in security camera footage in a tense standoff, were ethnic Roma, a local minority.

One of his victims’ relatives, not identified to protect her privacy, recalls how the night began: “Sitavichus and his friend come to Ogonyok. They’re relaxing, they’re drinking, they get in a fight with the ‘gypsies.’ Sitavuchus and his friend leave, and they say: ‘We’ll be back.’”

Arming himself with a Kalashnikov he had likely brought home from the war, Sitavichus returned to the restaurant with his friend, who brandished a knife. The men they had fought with were already gone — but that didn’t stop them from targeting the first ethnic minorities they came across.

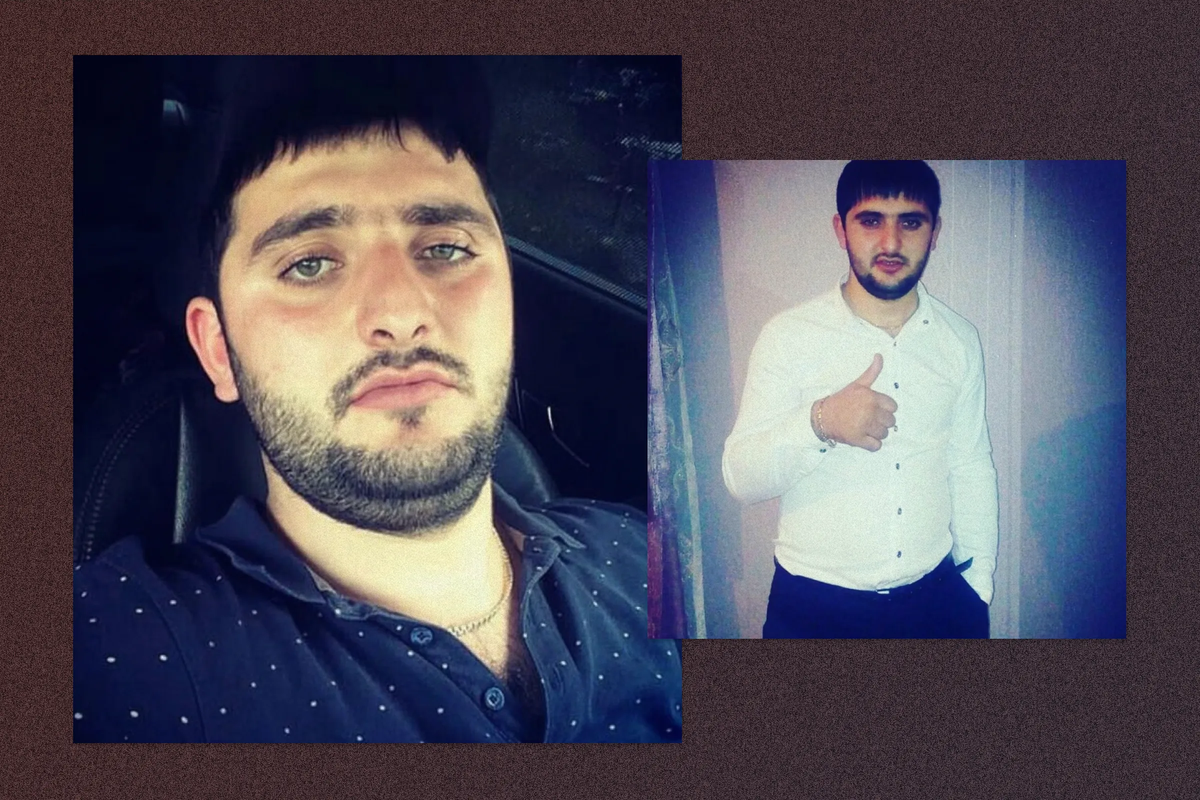

The first to fall was a young man named Artem Mirzoyan, who is of Armenian heritage.

“They shot my brother by the bar,” says his brother Arnold, “and they shot the DJ, who really had nothing to do with it. They came in like Nazis, firing at those who had beards. … They just wanted to shoot some dark people, non-Russians.”

Coming out onto the street, Sitavichus killed once more, shooting an 18-year-old Roma man who was sitting in a car listening to music with a friend. After briefly hiding in a nearby forest, he and his friend were arrested.

Despite the senselessness of the killings, many locals supported Sitavichus, who had been widely respected. But others saw him as nothing more than a murderer. The affair sparked what amounted to a one-village ethnic conflict.

“In our little village, where everyone knows each other, it became pure hell,” recalls Mirzoyan’s female relative. “It was scary just to go onto the street, because everyone was fighting each other. They started creating groups in the social networks [calling for] Russians to push non-Russians out of the village. It was so scary to read all of that… I didn’t even leave my house.” Sitavuchus’s friend Gaivoronsky also explains his actions in terms of ethnic conflict, while attributing his excesses to alcohol.

“There’s this Armenian-Gypsy organized criminal group, and they’re terrorizing this whole village,” he says, recalling unconfirmed rumors that some Roma men had raped a local girl in that same cafe. “It was a boiling point, you see? … The fact that he was drunk makes it worse, of course. All of our ‘truth-seekers’ drink a hell of a lot of vodka, and then they go to jail instead of solving things through the cops.”

Sitavichus was convicted of the murders and received a 21-year prison term. He would serve only four: In 2022, he took advantage of a Wagner Group offer to win his freedom by going to war. Two months later, he returned home in a closed coffin. He was buried in the local cemetery with military honors. To this day, locals debate whether he was a hero or a criminal.

“Every week I go to that village and go to the cemetery,” says Arnold Mirzoyan, the murdered man’s brother. “I see the flags, I see how Sitavichus was buried. How he’s being honored. It’s unpleasant, of course. Like a hero!”

“What kind of a hero can he be, if he killed three people?” says Mirzoyan’s other relative. “Just because he went to the war, that makes him a hero? No, a hero is something different. … For me it’s very strange, how a killer can go to war and come back and say ‘I’ve reformed.’ People don’t reform like that. It’s for killing that he went. It’s a war, after all.”

Sitavichus’s friend Gaivoronsky has no kind words for Russia’s leaders. “Those in the administration are worse than the [Ukrainians],” he says.”I’m not an imperialist. Our empire is aimed at the destruction of its own population. This madness needs to end.”

But this doesn’t stop him from justifying his friend’s decision to fight.

“You can’t view it from just one angle,” he says. “No one is valorizing what he did in that cafe, shooting people. But these criminals are the most effective [in the war] right now. They’re our heroes!”

“The Little Wolf”

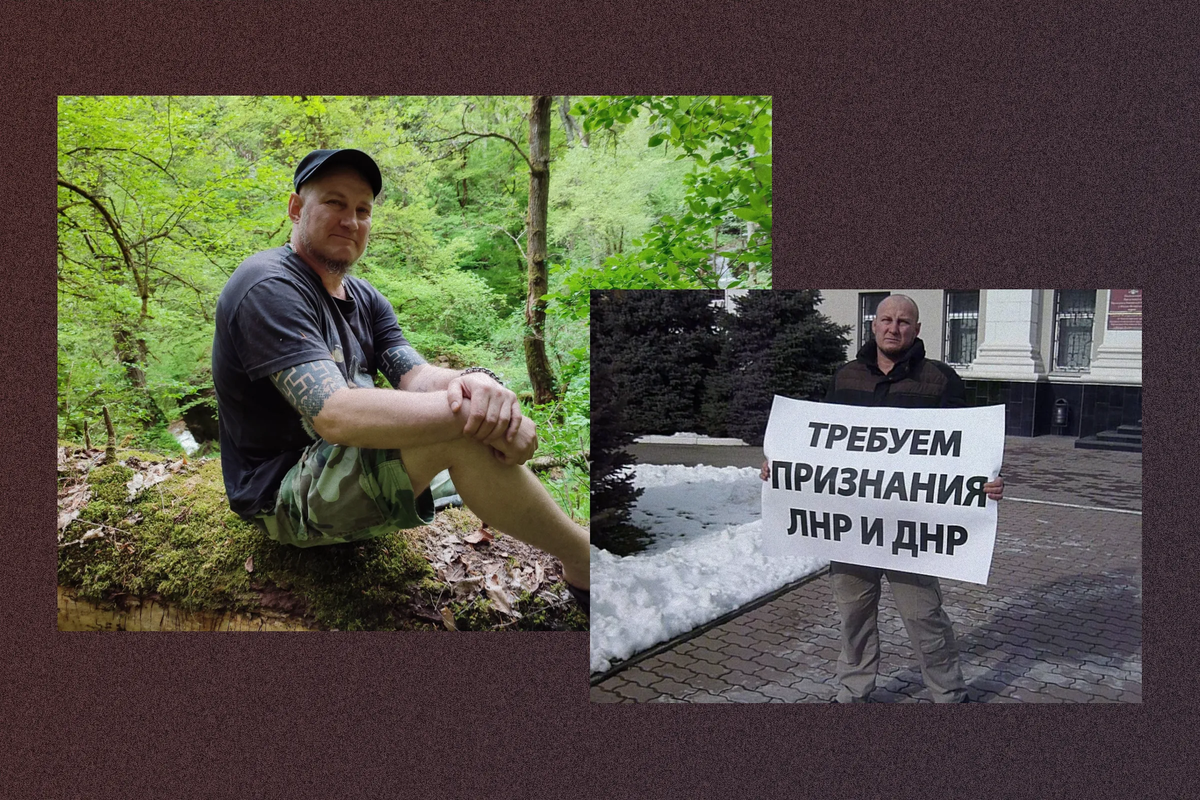

Yury Gavrishov met Ksenia Podkorytova in a correctional boarding school in the village of Konstantinovskoe in southern Russia. Both were orphans. They struck up a relationship, sometimes meeting in a house he was given by the government after leaving the institution.

But the romance wouldn’t last. In 2017, Gavrishov killed his partner in a fit of jealousy, striking her in the head several times with a brick.

Even today, her VKontakte page reads: “Yura, I love you very much. You’re my favorite husband!” The two were never officially married, but locals recalled a tumultuous relationship.

“He got stupid drunk, she cheated on him or something,” said a local resident, Vlad Ivanov. “So he went psycho and killed her.”

Gavrishov was the youngest of 10 siblings from a troubled family. “We were like little wolves — we raised ourselves,” remembers his older brother Nikolai. “Honestly, there was something wrong with him. Some kind of deviation. He was slow, didn’t catch on. He was the last of us, after all. Our parents were drinking a lot, and then he was born…” The Gavrishov siblings spent their childhoods in and out of boarding schools until their parents died and there was no home to return to. Several fared little better than little Yury, his brother recalls: Three of the brothers have died, one by suicide.

Yury Gavrishov hardly had a chance to experience normal life. He never learned to live independently, and never held down a job. After leaving his boarding school, he was sentenced to correctional labor for stealing propane tanks. Having murdered his girlfriend, the 22-year-old turned himself in to the police, and was eventually sentenced to an eight-year term. After landing in prison, he created a new profile on the VKontakte social media site. His status update read: “If you’re going to fuck, then only princesses.” He added the year his prison term would end: “2026.”

But he wouldn’t live that long. Last fall, Wagner recruiters came to his prison. He wrote his brother a single message: “That’s it, brother, they’re taking us in an airplane, we’re off.”

“I never heard from him again,” Nikolai says. To find out what had happened to his brother, he called a Wagner hotline. The voice on the other end reassured him: “If something had happened,” the dispatcher said, “you’d already know about it.”

He didn’t. Nikolai only learned of his brother’s death when he was contacted by an IStories reporter, who spotted Yury’s gravestone in a video of a Wagner cemetery hundreds of kilometers from his hometown, posted online by a local blogger. Nikolai lamented that the authorities hadn’t kept him informed, but seemed to have no strong opinions about his brother’s choices. Trying to convince Yury not to go to war would have been pointless, he said. “Every person has their own fate,” he said. “Probably this is how it was written for him.”

“Just a Thief”

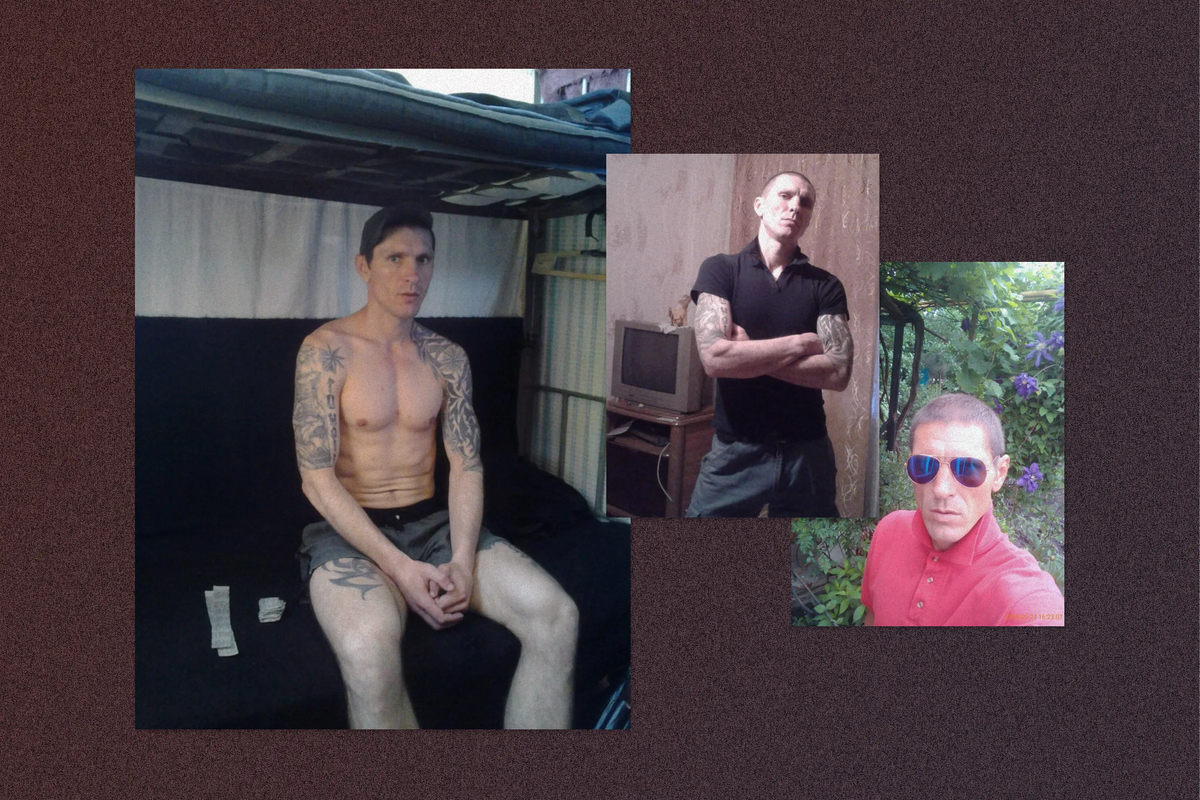

In the same Wagner cemetery lies another man whose aimless, difficult life was little different from Yury Gavrishov’s. In a photo he uploaded, Dmitry Vashchenko is sitting on a bunk, looking into the camera with surprise. His legs and forearms are heavily tattooed. He is in a prison colony, where he was a regular inmate, cycling in and out for much of his adult life.

“He comes out, he goes around the village for a month, and steals something again,” says Tatyana Orekhova, from whom Vashchenko once stole a cow. “Just a thief, and that’s it. No one ever said anything good about him. He was hardly ever here in the village. He was always in prison, always!”

Vashchenko’s criminal record confirms the story: Police records show he tried to rob a convenience store, stole a car, and stole three chairs from a neighbor. Like the Gavrishevs, the Vaschenko family also lived in poverty. In the village, they are not remembered fondly, but with some understanding. “They’re not evil. I don’t think they’d kill anyone,” says Orekhova, who decided not to file a formal complaint against Vashchenko after he stole her cow. “It’s just theft, with them. No one educated them. Their mother drank her whole life. They were restless, and no one needed them. So that’s how they lived.”

In 2020, Vaschenko got in more serious trouble after using a slingshot to throw bags of hashish and other drugs onto the grounds of a prison colony. He tried to explain his actions in court by saying that he had served time there and knew how much the prisoners craved drugs. But the judge was not amused, handing him a 10-year sentence.

After he was imprisoned, Alina Kolomeitseva, a local woman who had played a kind of parental role for Vaschenko, received a message from him: “If I had listened to you, I wouldn’t have been sentenced,” he wrote. “I understand that I’m a fuck-up. First I act, then I think. I’ll try to turn on my brains.”

“It was a normal family,” she recalls of the Vashenkos. “What happened? Maybe the ’90s? Poverty? The mother drank herself to death. Then the kids went sideways, somehow. She had kind of restrained them, and then — that’s it. One sister died. Another got wasted and hung herself.”

Vaschenko liked luxury, Kolomeitseva says. But he didn’t like working, and couldn’t keep the job she arranged for him. “He can’t live normally, he can’t go to work,” she says. “If not for the drugs, maybe some use would have come of him. But he went where he shouldn’t have gone. If a normal woman had crossed his path, straightened him out? If he had fallen in love? But he had nothing.” Vaschenko’s decision to join Wagner, she says, was a way to escape a life he had come to see as a dead end. “I think it was his only way out,” she says. “He went because this life was meaningless for him. Of course, that’s pretty big talk. Because this war has become a little meaningless as well.”

Polina Uzhvak, Sonya Savina, and the IStories data team contributed reporting. Some information about the Wagner recruits was provided by the staff of Lyubov Sobol, a Russian opposition politician.