Faces of Censorship

IStories found out who and why works for Russia’s main censor

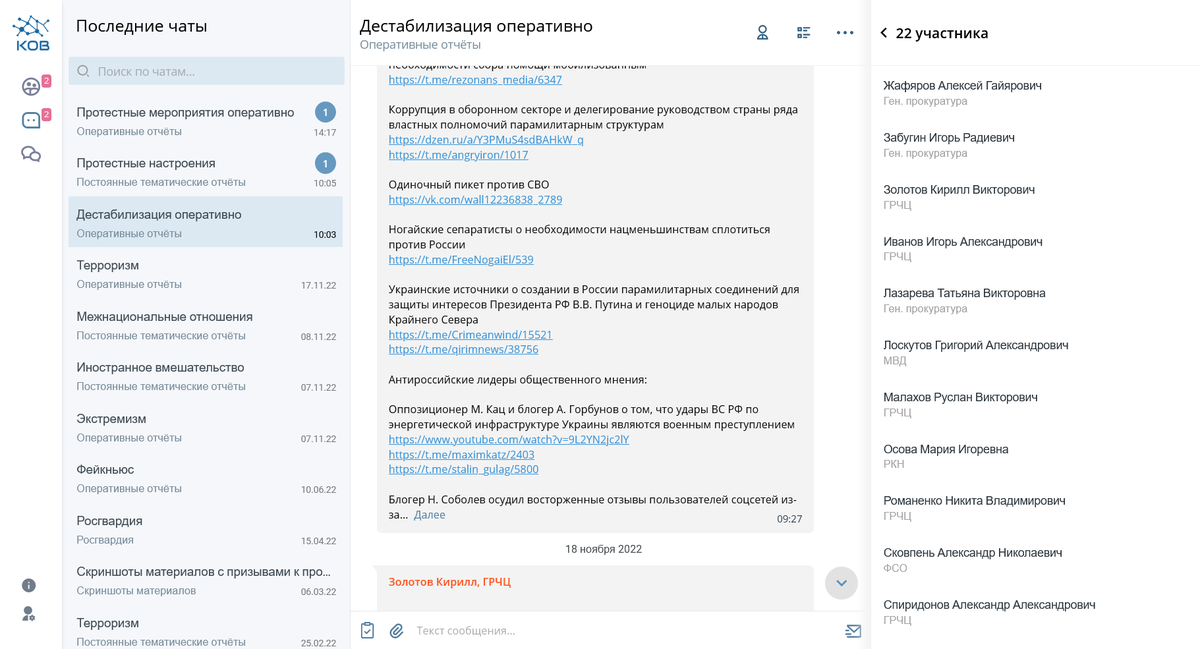

In November 2022, the Belarusian hacker group known as the “Cyberpartisans” hacked into the internal network of the “General Radio Frequency Center,” (GRFC) part of Russia’s main censor, Roskomnadzor (RKN). The hackers downloaded more than two terabytes of documents, correspondence and mail from employees, then handed it all over to journalists.

When GRFC employees learned about the leak they began to panic. They who compiled sheets to label journalists, artists, oppositionists and activists as “foreign agents,” developed programs to surveil Russians totally on the internet, and blocked independent media and memes critical of Vladimir Putin, were now afraid people would find out how they were assisting the regime, using propaganda to hide the truth about what is happening in the country from its citizens.

GRFC management even advised employees to change their passports, and promised to “discuss the possible centralized deletion of personal data through punching services [through such services, for money, you can get information about a person – for example, phone numbers, social media accounts, passport data, etc. — Editor’s note],” according to a report from journalists at Current Time, which referenced a source inside the department. The very next day, employees were informed that the administrators of “one of the key Telegram bots for data punching” agreed to delete data about them: “They quickly realized who they deal with and are ready to cooperate.”

Despite the GRFC leadership’s best efforts, IStories managed to track down and speak with some of the agency’s employees.

Get acquainted with the faces of Russian censorship.

“Not seen in discrediting relationships”

The GRFC is not a secret organization, but its employees fear publicity. In attempts to hide their identities or avoid open conversations with journalists, they not only wipe their data from punching Telegram bots.

30-year-old Kristina Mosenz, who is responsible for organizing media and social media monitoring at the GRFC, attempted to falsify her own detention so as not to answer uncomfortable questions. Her subordinates prepare information sheets of people and organizations to label them as foreign agents, and also compile reports on so-called "points of information tension" — events and publications that may cause public outcry.

When we called Mosenz by personal phone, a male voice answered: “I wish you good health! Kristina has been with us for two days already — detained for economic crimes.” The man, pretending to be a security official, asked if the police were looking for Mosenz, and advised them to make an official request to the Investigative Committee if they wished to speak to her. But a few days later, Mosenz herself picked up the phone and, when asked by IStories reporters about why she decided to work as a censor, she asked that we not call again.

Mosenz's employees monitor calls for protests in Russia, information about the war in Ukraine, criticism of Vladimir Putin and any other topics that the Russian authorities consider dangerous. These reports are sent by the employees of the GRFC “upstairs” — to the Prosecutor General's Office, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Federal Security Service, the Presidential Administration and other departments.

After the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the workload of the employees working in the GRFC’s monitoring department and related units picked up. They had to cancel some of their regular tasks, as a result: the GRFC temporarily stopped compiling reports on terrorism and “anti-Russian propaganda in the Baltics,” stopped monitoring the sale of fake coronavirus vaccination certificates, suspended monitoring of violations during broadcasts by the largest Russian TV channels, and ignored television shows and films “with a drug theme.”

Despite this reduction in some responsibilities, employees began to leave. In mid-May, a vacancy for a senior shift supervisor in the on-duty monitoring service opened at the GRFC: as explained in the application, “due to the multiple increases in the number of tasks and stressful conditions,” several people left the department at once. However, new workers replaced the departed ones. In February 2022, the GRFC planned to recruit 102 new employees to the department for monitoring media and social networks, and expand its total staff by 450 people. Before hiring future employees, they checked and compiled testimonials on them, at which time they expressly indicated that “no information was found about the candidate’s participation in events in support of A. Navalny or communication with opposition figures.”

In total, more than 5,000 people work at the GRFC. We’ll introduce you to some in leadership positions and those directly involved in censorship.

Censor factory

The GRFC recruits new staff from among students at the largest universities in Moscow. They decided to ramp up recruitment of students at the end of 2021 due to the “tense situation with labor resources, expressed in the outflow of qualified personnel.”

Already, the GRFC is cooperating with Moscow State University, Moscow State Law University, and the Financial University under the Government of the Russian Federation, among other major educational institutions. GRFC employees conduct classes at these universities and take students on as interns, teaching them about the basics of Russian legislation as it relates to the media, the specifics of determining the status of a foreign agent, and how to use artificial intelligence to track information. They are taught to look for “points of information tension” and monitor media and social networks manually.

Interns are used for “routine” and “labor-intensive non-priority” tasks. For example, in April 2022, an intern from the political science department at Moscow State University compiled a report on the editor-in-chief of the Dozhd TV channel Tikhon Dzyadko, in which, among other things, she indicated that Dzyadko was baptized and “is a character in the famous Internet meme, ‘My Semyon.’”

Here’s a description of how, according to another intern, some Russian media can be characterized:

- Cosmopolitan magazine “incites hatred not only on gender, but also on national grounds”;

- Republic internet portal “is a stronghold of Russophobia and is filled with an extremely toxic audience ready to harass you for any praise of Putin”;

- Voice of America — “a puppet American radio station that participated in the information and psychological war against the USSR.”

Particularly distinguished students receive offers to complete test tasks for full-time employment at the GRFC. Some are asked to describe the conflict between the head of Chechnya, Ramzan Kadyrov, and the Yangulbaev family (Chechen authorities consider the sons of the retired federal judge Saydi Yangulbaev, Abubakar and Ibragim, to be involved in running the 1ADAT Telegram channel, which criticizes authorities and Kadyrov personally. — Editor’s note). Others are asked to monitor reports about the health of Vladimir Putin. “If possible, identify distributors and primary sources, and media figures who also participated in the dissemination of such fakes. Refrain from declaring your political views. Maximum factuality and neutrality,” Kirill Zolotov, head of the on-duty monitoring department, wrote to the candidate.

IStories contacted students who received jobs in GRFC after the start of the war in Ukraine. Alexandra Zinger, a political science student at Moscow State University, hung up after hearing the question. Her colleague, a 22-year-old student in the same department named Anastasia Sheremeto, denies her work as a censor:

— Do I understand correctly that you are monitoring social media networks and protest actions?

— No, no, you’ve made a mistake. I don’t work, I’m studying law.

— I saw that you were doing a test task at the GRFC about the conflict between Ramzan Kadyrov and the Yangulbaevs, and were sent employment documents.

— “No, you imagined that,” Sheremeto told the IStories journalist before hanging up.

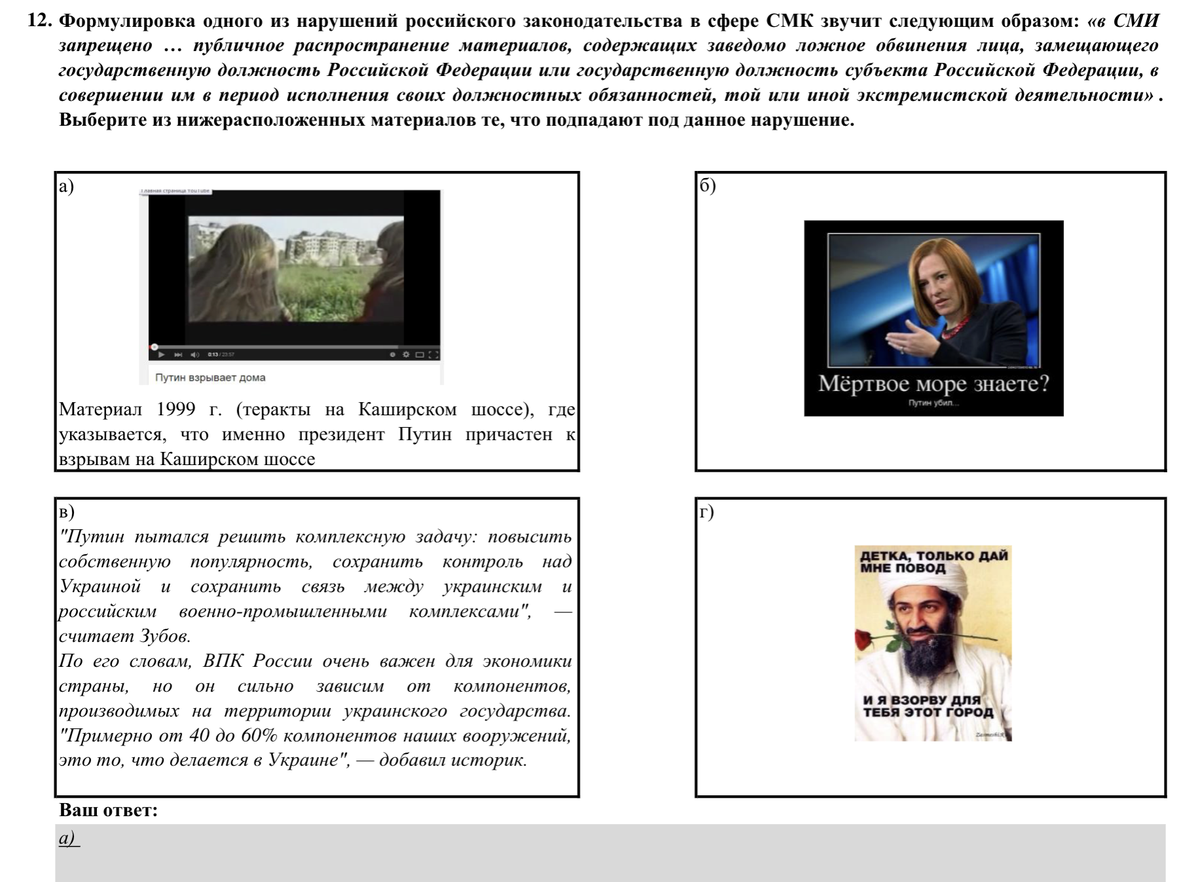

In addition to trial assignments, candidates are offered tests. They’re asked if a video called “Putin blows up houses” about terrorist attacks in Russia in the late 1990s is offensive to the president, or whether an invitation to a demonstration by Alexei Navalny would be a call for riots. They’re asked which among the words “fuck,” “shit,” “bitch,” and “ fucker" is not obscene.

The GRFC fights with other government agencies to hire students. “I received 10 selected resumes from the Faculty of Political Science at Moscow State University. More could be gotten, but people there already have offers or are waiting for them (mainly from the Presidential Administration) and may run off,” complained Alexander Spiridonov, deputy head of the on-duty monitoring service. However, not everyone can be accepted as censors. The GRFC is not prepared to hire “politicized students,” and preference is given to candidates with “experience in state structures, preferably law enforcement or close to law enforcement.”

Not everyone likes the interns — one GRFC employee, dissatisfied with his colleague, asked the boss: “who’s this fuck?” The deputy head of the on-duty monitoring service, Alexander Spiridonov, answered him: “These are the new realities. In the DMSMK [department for monitoring mass media] and DRZI [department for maintaining registers of prohibited information] they recruited a bunch of newbies, including some as group heads.”

How much does an Internet censor earns

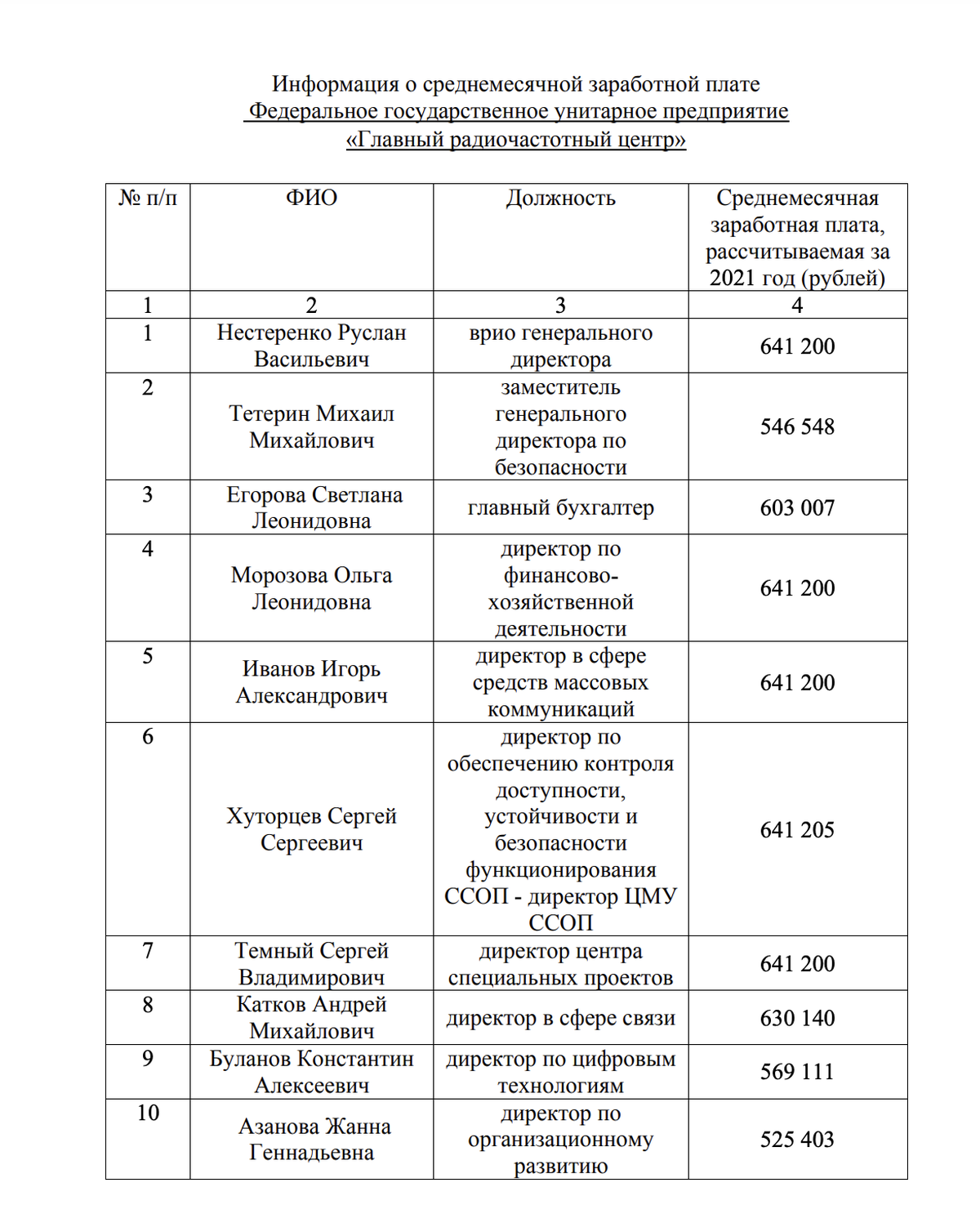

Managers at the GRFC, for example, the director of mass communications, Igor Ivanov, earn at least 600,000 rubles (≈7950 US dollars at the exchange rate of March 2, 2023) per month. Beginners are paid from 40,000 rubles (≈530 US dollars) monthly, and department heads 100,000 or more, excluding bonuses. The average monthly salary of GRFC staff is 81,000 rubles (≈1070 US dollars).

There are employees for whom the GRFC is ready to make exceptions, however. For example they managed to get a salary of 250,000 rubles (≈3310 US dollars), for the head of the machine learning department, Andrei Nevzorov, — “so that he doesn’t quit,” as his colleague Anastasia Volkova, from the digital transformation department, put it.

It isn’t just IT workers that become censors — scientists do, too. For example, a group of scientists from Russia’s top technical university, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, under the leadership of the head of the Department of Machine Learning and Digital Humanities Konstantin Vorontsov, wrote a research paper on the development of the Vepr system which, using neural networks, is designed to find calls for protests on the internet, "positive portrayals of LGBTQ,” criticisms of healthcare and education systems, comparisons of living standards between Russia and the West, and the “cowardice of modern Cossacks,” among other topics. We wrote more about how Roskomnadzor implements artificial intelligence for surveillance in this report.

Vorontsov at first listened to what IStories wanted to discuss with him, asked to call back, and then stopped answering calls.

The first rule of the GRFC is: you do not talk about the GRFC

The GRFC workers’ refusals to speak with us is not just due to a fear of publicity around their work as censors, but also because of the instructions that newcomers receive when they join. These state that the department “fully supports the right of employees to freedom of speech and self-expression on the internet.” It comes with a caveat, however — employees are asked not to publish “provocative personal content,” and refrain from commenting on their work and from public criticism of Roskomnadzor or the GRFC itself.

Most employees really do make an effort to not talk about their work. After the data leak, many closed their social media profiles and changed usernames.

Only a few still dare to at least briefly speak with journalists. For example, 37-year-old Olga Prudnikova is the head of the federal mass media monitoring department. She collected information sheets for labeling people as foreign agents from other employees, and gave out instructions on how to surveil the media. For example, she ordered employees to find materials that are “negative in relation to the current government and the special military operation” on the website of the independent media outlet, Novaya Rasskaz-Gazeta. A week later, the project website was blocked.

— “IStories, yeah, we know you... Do you think that I’ll just tell any journalist I meet about my work?” Prudnikova asked.

— I would like your personal opinion on this. What do you see as the importance of this work, why do you do it?

— Well, probably the same reason as you. Everyone earns money however they can.

— So you're doing this for the money?

— “No, I didn’t say that, it’s not for the sake of money,” Prudnikova ended the conversation, refusing to answer further questions.

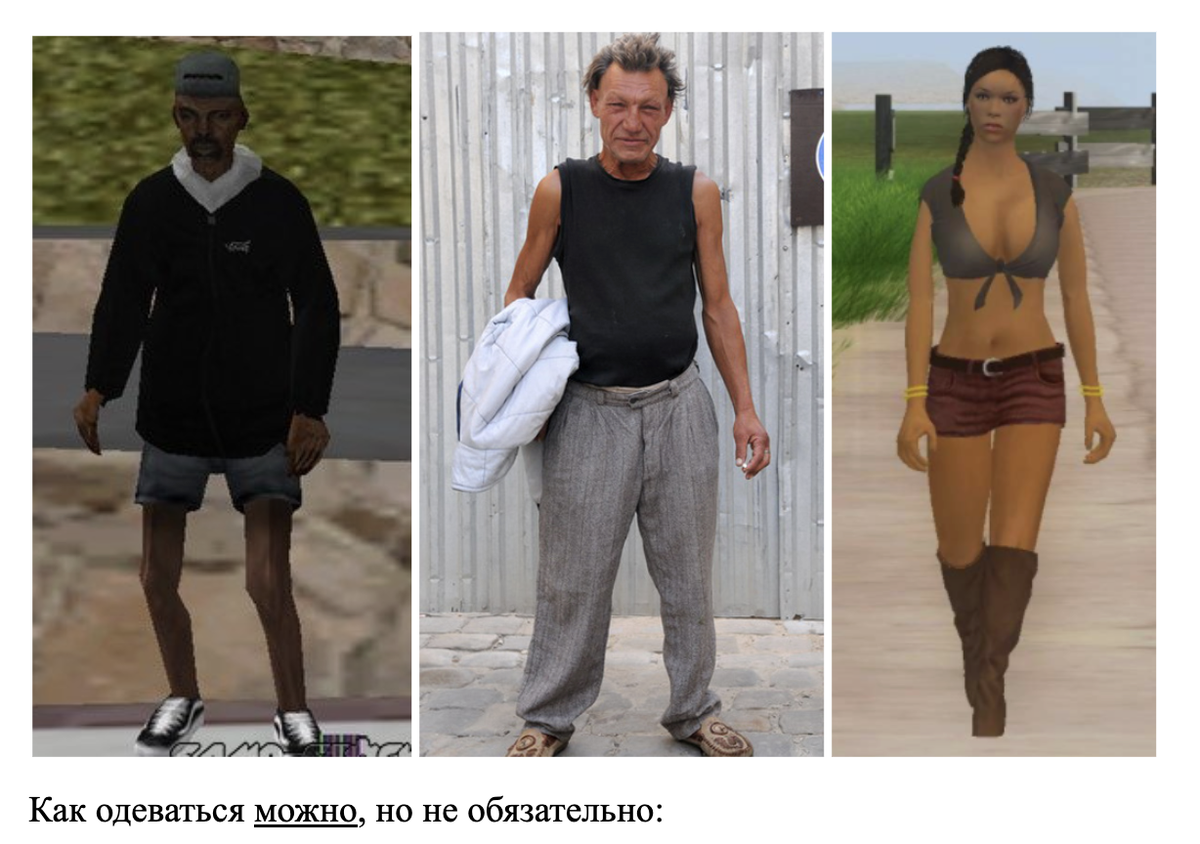

In addition to keeping quiet, employees are also advised to follow a dress code. One version of the beginner's guide has examples of how not to dress for work and how you may dress — but you don't have to.

Among the benefits GRFC employees receive are medical insurance, travel and food compensation amounting to 4,800 rubles (≈64 US dollars) monthly, and financial support in the event of a child’s birth or the death of close relatives. But the biggest perk is protection against mobilization.

Initially, GRFC employees weren’t granted a deferment, and some were given draft summons right at the workplace. About 2,000 of GRFC employees could fall under risk of the draft — almost half of the staff. However, the head of the digital transformation department, Denis Kasimov, launched an active effort to prevent the censorship workforce from being taken to the war’s frontlines. Apparently, he succeeded, and was even offered a bonus for this.

“To date, it’s become possible to achieve an unambiguous deferment for some employees of the GRFC, primarily those who are at risk, especially those with combat experience and military specialties [...]. In connection with the foregoing, I consider it appropriate to reward Denis Kasimov in the amount of monthly salary payment,” the memo says.

“They deprive us of pennies for grub.” What do staff complain about?

Despite all these bonuses, not everyone likes the working conditions at the GRFC. Employees complain about the increase in workload, decrease in income and the disregard of the management.

In March 2022, Denis Kasimov, who achieved “deferment” from mobilization, wrote that it was uncomfortable for employees to use some of the computer programs, but Vadim Subbotin, deputy head of Roskomnadzor, didn’t care: “Subbotin doesn’t give a damn about the fact that users are not comfortable. Just let them work."

Duty service officers Konstantin Malinin and Denis Palagichev discussed that their manager, is a “dumb fucker” who’s “afraid of everything,” and makes them send many reports about criticism [of the president] to the Prosecutor General’s Office, even based on old publications. According to them, there is more and more senseless work, and salaries are getting worse: “We’re already doing the whole cycle — monitoring, adjusting the legal framework, making reports... yet the salary is only getting smaller. [...] We’re sitting here, collecting pennies, they’re even depriving us of these pennies for grub.” Malinin even wanted to quit: “I gave a lecture at MGIMO the day before yesterday and felt an acute desire to get fuck out of here. It’s incredibly acute, especially when I later looked at how every word was coordinated by [Roskomnadzor head] Lipov (!!!!) at the Rosmolodezh’s lecture on information wars.

In a conversation with IStories, however, Konstantin Malinin said that he’s satisfied with his work.

Judging from correspondence, the censors themselves understand that their work is not prestigious. “The image of the Roskomnadzor among IT people plays against their interest in us,” wrote Ivan Zuev, the former head of the department that maintained registers of prohibited information, discussing the prospects for inviting artificial intelligence experts to cooperate with Roskomnadzor.

But there are still those, too, who believe they’re doing important work. Take Ruslan Malakhov, former shift supervisor in the duty monitoring department of the QMS, for one. He reported to the Prosecutor General's Office about publications that discussed the deaths of civilians, the loss of Russian soldiers and other unpleasant facts about the army. It was his work account that the hackers used to gain access to the entire GRFC system. In correspondence with a journalist from IStories, he said that he quit the censorship department a month ago for reasons unrelated to the leak.

Malakhov decided to share why he works as a state censor. “For all my absolutely healthy dislike for certain phenomena like corruption, hiding facts about it and the like, it seems to me that the State has the right to protect itself in a way that is accepted by the majority of society in it,” Malakhov wrote. “But even if the state, for example, does not function the way I’d like, then I’d like to solve these problems at home [in my way], do you understand?” Ruslan did not answer the question why, in his opinion, Russians shouldn’t learn about people injured or killed in the war, or any other facts that do not fit into the pro-Kremlin narrative.

Another ideological employee is Dmitry Lyapustin, a specialist in the department for monitoring mass media. This department is tasked with checking whether media labeled foreign agents have placed the required disclaimers on all their articles and social media posts (“This message was distributed by a foreign agent ...”).

In a conversation with a journalist from IStories, Lyapustin demanded to know where she was, called her an "enemy of the Russian state" and hung up the phone several times. He justifies his censorship work by the fact that “he has an extremely negative attitude towards fakes and is doing his job — compliance with the law in the field of mass communications.” Lyapustin does not seem to think about false information in state-controlled Russian media.

Why do people choose this job — being directly involved in blocking independent media, monitoring posts and comments critical of the authorities and reporting them to the Prosecutor's Office? Associate professor at the Faculty of Social Sciences at the University of Amsterdam, Anna Fenko, explains that not only high wages, but also low wages and unpleasant working conditions for people working in censorship, oddly enough, may contribute to ideological adoption.

“[Censorship workers] fall into two broad categories. The first is absolute cynics, and they work for money,” said Fenko. “They don’t believe in anything, they play by the rules. They do what they’re paid to do. And there are also people who are paid less. This is a very interesting group, one that doesn’t have enough material justification for such dirty work. And they begin to believe that they’re doing everything right — otherwise they would have so-called “cognitive dissonance.” One way to resolve this dissonance is to simply convince yourself that these deeds are not negative, but actually quite good.”

When the regime changes, these people most likely will not feel any guilt about committing crime — engaging in censorship, which is prohibited by the Russian Constitution. “Let’s imagine that in some miraculous way the regime changed in the country, and these people were told, ‘thanks, you’re free to go,’ Fenko continued. “Will they feel guilty about their past? Historical experience shows that most likely not. They immediately forget everything they were doing. They’ll only remember how they secretly criticized some of the frantic actions of this regime in their kitchen, especially the idiotic orders of their ex-superiors. They will convince themselves, and then others, that they’ve been opponents of the regime all their lives.”

Editor: Alesya Marokhovskaya