“I’m Never Going Back to That Hell. I Don’t Want to Give Birth in This Country Anymore”

In Russia, one baby dies during labour or pregnancy every minute — an IStories investigation

For the entire twenty-year period of Vladimir Putin’s reign, there has been a conscious effort to increase the birth rate in Russia. In his latest Address to the Federal Assembly, the president announced an increase in benefits for pregnant women. Following this, more than twenty women from various regions of the country whose children had either died during labour or suffered birth trauma published a video appeal to Putin requesting that he address the poor quality of medical care given during childbirth.

Important Stories has analysed data concerning maternal and infant mortality rates and talked to families whose children either suffered trauma or died during labour. Today we are going to tell you why, despite all the government’s promises, women in Russia are still scared to give birth.

How We Calculate It

To evaluate the quality of medical services for women in labour in Russia we are analysing several statistical indicators.

Infant mortality is the death of children under the age of one. The coefficient indicates the number of infant deaths for every 1000 newborn babies in one year. Each year the Federal State Statistics Service publishes its own infant mortality data. For an international comparison, we are using data provided by UNICEF for the year 2019 (Infant Mortality Rate figure).

Not every case of infant mortality is directly linked to childbirth. Therefore, there is another important figure to consider: perinatal mortality—the number of foetal deaths beyond 22 weeks of pregnancy and the number of deaths among newborn babies within the first seven days of life for every 1000 total births in one year. This indicator includes stillbirths—babies born without any signs of life after 22 weeks of pregnancy. This data is published by the Federal State Statistics Service.

There is one more important figure: the number of abortions. Abortion figures are published by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation and include both artificially terminated pregnancies and spontaneous abortions (miscarriages), which we have also counted as instances of a mother losing her child.

The Ministry of Health also publishes data concerning the health of newborns—for example, the absolute number of sick infants and those who are born sick per 1000 live births. ‘Birth Trauma’ as a cause of morbidity in infants deserves special attention.

The coefficient for maternal mortality is the number of women who have died from complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period for every 100,000 live births. The data for this is published by the Federal State Statistics Service. For an international comparison, we are using data provided by the United Nations (UN) for the year 2017—the last available period.

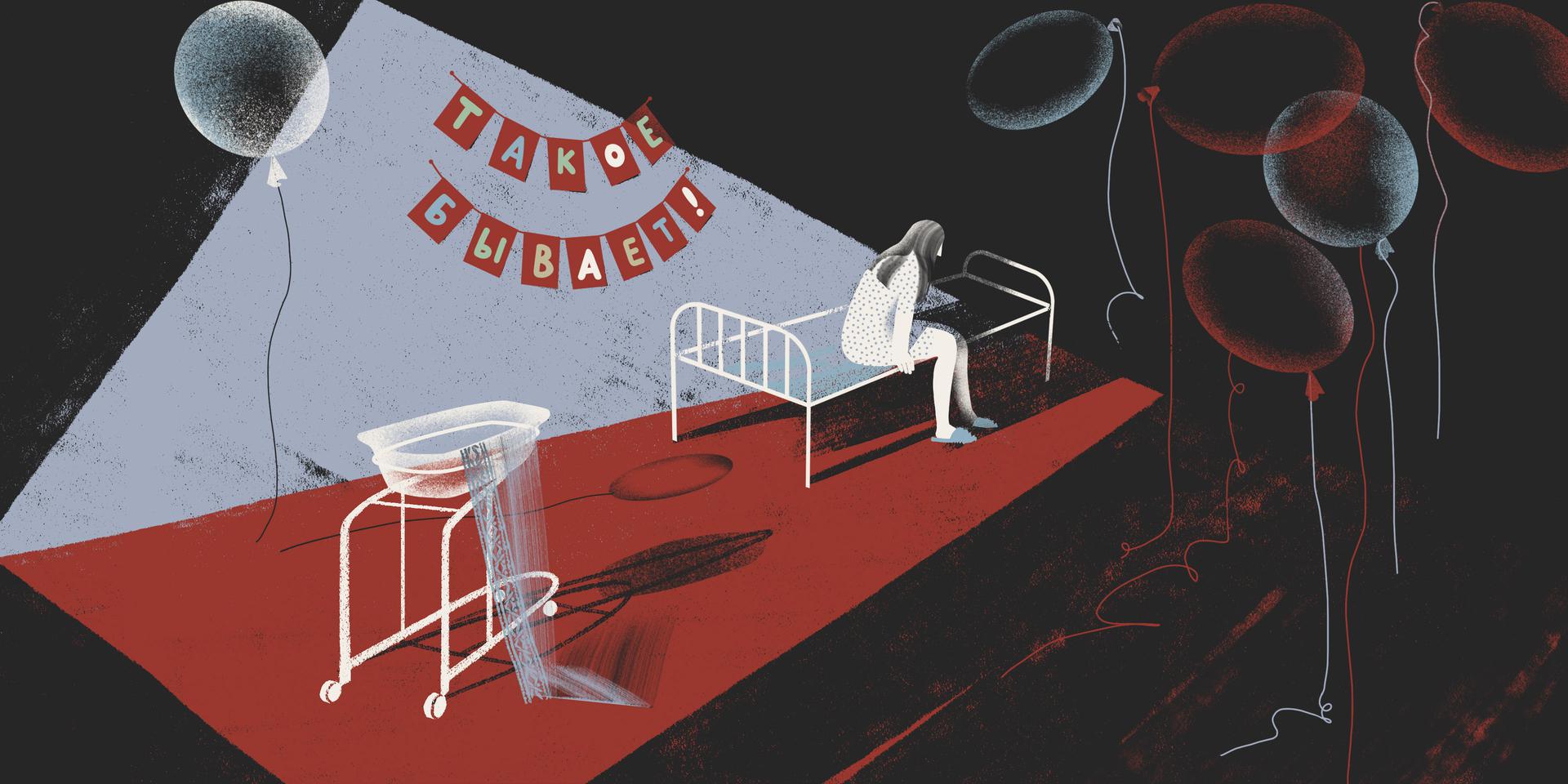

‘It happens’

In 2019 Tula mother Anastasia Asaulko’s newborn daughter died twenty days after her difficult birth. Anastasia tried to get the doctors to answer her question: How could this have happened to a healthy baby that was carried to full term? The doctors, she said, replied with, ‘It happens’. Anastasia’s case is just one of the half a million similar tragedies that befell new mothers in 2019 alone. In Russia, one family is faced with the loss of a child (if you consider the point of conception to the child’s first birthday) or the termination of a pregnancy every minute.

Every fourth pregnant woman in Russia loses her pregnancy through abortion or miscarriage. More than 500,000 pregnancies failed for these reasons in 2019. Another 8,000 children were stillborn (according to Federal State Statistics Service data). Up to a third of children born alive were born with morbidities (according to Ministry of Health data)—that is more than 400,000 infants whose lives are now dependent on medical care.

In Russia, a stillbirth occurs or a newborn dies (either during birth or in the first year of life—ed. note) every thirty minutes. The Infant Mortality Rate in Russia is gradually decreasing, but to this day it is still significantly higher than in most developed countries. For example, in 2019 the Infant Mortality Rate in Finland and Norway was 1.8 and in Iceland it was 1.2. In the same year, the Infant Mortality Rate in Russia was several times higher—five in every 1000 newborns—the same as in Chile, Bahrain, North Macedonia, Qatar, Sri Lanka, and Malta.

In 2020 more than 6,000 children under the age of one died. On average this is 4.5 cases for every 1000 infants. But in almost half the regions in Russia, the level of infant mortality is significantly higher than in the rest of the country. Chukotka Autonomous Okrug has the highest figure of 15.1 cases for every 1000 infants. And while the general figure for the country may be decreasing each year, in some regions it is doing the opposite. ‘Figures such as infant and maternal mortality rates are KPI (Key Performance Indicators—ed. note) of the quality of obstetrics services across the country and in the regions,’ says Anastasia Novkunskaya, a sociologist from The European University who specialises, among other things, in the study of obstetrics services.

‘I couldn’t cross the threshold of my apartment; the baby’s things were in there’

For Anastasia Asaulko and her husband, the pregnancy was long-awaited: they had been trying for five years. ‘Our whole family was waiting for this baby. The pregnancy yoga classes, the photoshoots, the courses—everything was for the baby and me. Everything had been bought: The stroller, the baby grows. Everything had been washed and ironed,’ remembers Anastasia. When she gave birth in 2019, she was 26 years old.

The Asaulko family chose the Tula Regional Perinatal Centre for the birth—the only one in the region. Anastasia thought the centre would have qualified professionals, good equipment and facilities, and an emergency room. According to her, before the IVF (in vitro fertilisation) procedure, the Moscow doctors routinely carried out thorough examinations of the couple’s health: ‘We had to be like astronauts: No infections, no health issues,’ Asaulko says. During the pregnancy ‘everything was normal, like with most women’.

Her water broke three days after Anastasia was admitted to the perinatal centre, but the contractions didn’t start. The doctors gave her two lots of pills to induce the birth, set up an oxytocin drip (a hormone administered to women in labour to stimulate contractions—ed. note), and held multiple consultations to choose how to deliver the baby.

All this time an electronic foetal monitor (EFM) was hooked up to Anastasia’s stomach to monitor the foetus’ heartbeat. She spent around eight hours waiting for the contractions to start and at that point, she noticed that the EFM was now showing four beats, whereas before then the figure had never dropped below nine (the EFM works on a scale of one to ten. A figure lower than five is considered a deviation from the norm—ed. note). ‘I was already panicking, I demanded: “Do something, the contractions aren’t coming and the baby is suffering”.’ Anastasia asked the doctors to perform a caesarean section so that the ‘baby wouldn’t suffer’, but they said ‘you’ll give birth yourself’ and administered a second oxytocin drip, as well as an epidural anaesthetic.

After that, in Anastasia’s words, she ‘was left completely alone’. The left side of her body was numb—she could not move her arm or her leg. ‘As I understand it, we missed the moment when I needed to start pushing, nobody told me what to do. And when I started crying for help because I realised I was giving birth, it was too late already. I saw on the EFM that the baby didn’t have a heartbeat, there was just a flat line there. I started screaming, they were saying: “Push.” “Why’s there no heartbeat?” I screamed. Nobody answered me.’ After that, Anastasia says, the doctor who was delivering the baby pushed on her stomach so the baby would come out.

Then the doctors took the baby to the emergency room. The baby girl was born in a serious condition with asphyxiation and hypoxia (these conditions are characterised by a lack of oxygen—ed. note). Anastasia says she saw the fear in the medics’ eyes: ‘I saw the way they were acting and felt twice as bad. I realised they didn’t have a clue what was happening and didn’t understand how it had happened. One of the doctors told me, “We didn’t know we were limited on time”. Who was supposed to know, then, me? This was my first time giving birth and I didn’t know how to do it. There should have been somebody with me at all times, a midwife at least, and the doctor should have been coming to see me every half an hour. But there was no one, and that’s why it turned out like it did.’

Anastasia’s newborn daughter spent twenty days in intensive care. ‘My husband and I went there, took books, read fairy tales to her, songs and poems, and prayed, and we baptised our daughter,’ Anastasia says as she recalls their visits to the intensive care unit. ‘It was a living nightmare: Seeing your baby lying there, helpless, covered in all these tubes, and there’s nothing you can do, that despair—you want to help your child, but you can’t. It’s so painful. And sad, and you don’t know what comes next.’ During this period the couple tried getting help from other doctors and they wanted to take the child to a different clinic. But the specialists from Moscow told them they couldn’t take their daughter anywhere in that condition—she wouldn’t make it; she wouldn’t survive.

And that’s what happened, says Anastasia. The Tula Perinatal Centre was shut down for sterilisation (planned sanitary and hygienic treatment—ed. note), and her daughter was transferred to the Tula Children’s Regional Clinical Hospital. ‘We got there but we could already see that the baby’s condition had got worse. Both me and my husband said goodbyes to her there. I already knew there were only a few hours left. The baby survived in that hospital for twenty-four hours,’ Anastasia tells us. ‘At that point, we were living with my parents because we couldn't go back to the apartment. The baby’s things were in there: the stroller, the cot; I couldn’t cross the threshold of my apartment. They called my husband [from the hospital]. I heard him crying. He didn’t need to say anything to me. The only thing I remember is falling,’ she says, remembering the moment she was told her baby had died.

‘I’m on my way to give birth and I’m thinking: Will me and my baby survive today or not’

Anastasia believes the doctors who delivered the baby are to blame for her daughter’s death: ‘For some reason, they were all passing everything off to each other that day. Perhaps it was because it was a Friday, everyone was rushing to get home,’ she contemplates.

After the funeral, Anastasia decided to go through the courts to find out the real cause of her daughter’s death: ‘Back when my daughter was in intensive care and was still alive, the Direct Line with Vladimir Putin was on the television and I recorded a video message, wrote him a letter, asking him to help my child. I didn't get a response. Once we’d had the funeral, I knew I had to do something. I couldn't just leave it like that, with this question of how it happened hanging in the air. And the answer I’d been given—"It happens”—didn’t fit right in my head. A healthy baby, and that’s the outcome?’

‘We live in a modern world with so much technology, but they still can’t deliver babies.’

The forensic doctors confirmed that the medics had made mistakes during the birth (Important Stories has the examination report). Firstly, their actions led to ‘uterine hyperstimulation’: The speed at which Anastasia was being given oxytocin was increased—this was not in line with the requirements of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation’s clinical guidelines for delivering babies. According to the examiners, this was what could have caused the foetal hypoxia.

Secondly, the doctors did not carry out constant observation of the foetus’ condition—this did not allow them to diagnose the hypoxia and perform a timely delivery. As the examiners write, if the doctors had picked up on the hypoxia on time and carried out a vacuum extraction (this is an operation to artificially extract the child using a special device—ed. note), ‘there would have been a chance of the baby being born alive with less severe asphyxia and a more optimistic life prognosis.’

According to the examination report, even though ‘the medical care that was carried out was not done so to the proper extent or on time, and was not in accordance with the requirements’, and that the doctors’ mistakes enabled the development of foetal hypoxia and prevented the delivery being performed on time, all of this together could not have been the direct cause of the child’s death.

Alla Badaeva, the Head of the Department of Obstetric Pathology of Pregnancy at the Tula Perinatal Centre and the doctor who delivered Anastasia’s baby, refused to discuss this case with Important Stories. The centre’s Medical Director, Oleg Cherepenko, who also took part in the birth, also refused to talk to us about this.

Right now, Anastasia is continuing her efforts to sue the doctors. ‘I want these people to not make any more mistakes. My mum said to me: “They made a mistake, they knew that; I could see it in their eyes, they probably won’t do anything like that again”. But I know there will be other cases after mine, I know they’ll do it. I know they’ll carry on taking risks,’ says Anastasia.

Anastasia managed to get pregnant again after the tragedy and now she and her husband are raising their son, Arkhip. She was scared to give birth a second time. ‘When I found out I was pregnant again, it should have been a blessing, but for me, it was a disaster. I spent the whole nine months thinking the same thing would happen again. I didn’t trust anyone. I asked to have a caesarean, it was much easier that way, and I gave birth to a healthy baby. I cried with joy. But I know we could have had two blessings; our daughter would also have been running around now, but she’s not,’ Anastasia says. ‘We live in a modern world with so much technology, but they still can’t deliver babies. And I don't want to give birth again. Seriously, I went in there thinking: Will me and my baby survive or not. What is that about? No, I’m not prepared to go through that anymore, especially not with the current doctors.’

‘Why did you come to give birth so early?’

Yekaterina Pulcheva from the town of Shchyokino in Tula Oblast lost her twins in the same Tula Perinatal Centre in 2017: The boy survived for three days after the birth, and the girl for two weeks. According to Yekaterina, the doctors at the perinatal clinic had apparently got her date of delivery wrong and had caused premature births: The babies were born at eight months. ‘The doctor who delivered the baby started shouting [at me]: “He’s premature, he’s not ready, why did you come to give birth so early?” But what does “I came to give birth” mean? I didn’t go to them myself, the birth was planned, it had all been decided by the medical staff,’ says Yekaterina. Three days later Yekaterina was informed that her son had died. ‘We managed to baptise him at five o’clock and at seven in the evening they told me our boy had gone,’ Yekaterina remembers.

Her daughter’s condition worsened; she fell into a coma. Yekaterina tells us that she tried to help her daughter and transfer her to another facility, but the doctors at the Tula Perinatal Centre wouldn’t discharge the child for a whole month: ‘We were prepared to pay for the baby’s stay and the transportation; we were ready to do everything to save our baby. To which they said this wasn’t necessary yet, that they were dealing with it, that they had consulted the doctors at the Moscow clinics, that they wouldn’t take such little ones [there]. When we started kicking up a fuss—sick or healthy, we were going to fight for our baby—they gave me the discharge papers. And the next day, we had an appointment at the Morozovsky Hospital [in Moscow] for a consultation with one of the main professors. We were already at the door when my phone rang and they told us our daughter had died. We still have questions about why she died at that exact moment. Not earlier, not later, but right then, just as we were ready to set off to the clinic.’

After what happened the Pulchev family sued the doctors at the perinatal centre. ‘My husband and I have been trying to get through all this for a long time. At first, both of us only had one question: For what? Then, some time passed, and we had another question: Why did it happen to us, why did it happen to our children? The doctors apologized for being condescending, disrespectful, but to this day they haven’t admitted their guilt.’

Like in Anastasia Asaulko’s case, the forensic doctors found mistakes in the doctors’ actions (Important Stories has the examination report): Incomplete examination of the pregnant patient, delayed prescription of treatment for both children, and a lack of foetal heart rate monitoring during the birth. All of this led to an erroneous diagnosis and inadequate methods of treatment, but, in the examiners’ opinion, this alone could not have caused a deterioration in Yekaterina’s condition and the deaths of the children.

In April 2021 the Tula Ministry of Health reprimanded Oleg Cherepenko, the director of the perinatal centre, for ‘insufficiently monitoring staff actions’. Then, in that same April, five women filed a complaint about the work of the doctors at Tula Perinatal Centre in a joint video appeal. Following this, an investigative committee opened a criminal investigation into ‘Neglect of Duty’—it concerned cases that happened at the centre between 2017 and 2021.

After the death of her twins, Yekaterina Pulcheva managed to give birth to a healthy baby—also in Tula, but in a different maternity clinic and through a different delivery approach. ‘If there is a risk that there is something [wrong] with the mother or the baby, they go straight to an emergency caesarean; they don’t allow for irreversible mistakes that leave the child or the mother disabled,’ she says. According to Yekaterina, after what happened, she was scared to give birth again: ‘I was really scared to give birth, scared that we would have to go through it all again, wait all that time and that something would happen again. When Polina was born and we held her in our arms, we felt all these happy things, we felt that we had become parents. We started particularly feeling what had been taken away from us, what the maternity clinic had taken from us. How much joy they have deprived us of. My husband and I often think about the other babies, the twins, what they would be like now; there would have been three of them, a little nursery. It might have been three and a half years already, but you don’t forget something like that,’ Yekaterina says.

‘They told us straight away that she would die’

According to data from the Ministry of Health, one in three children in Russia is born sick. That’s 461,000 children in 2019 alone. In certain regions the situation is worse still: For example, in Nenets Autonomous Okrug, Kabardino-Balkaria, and Novgorod Oblast more than half the children born in 2019 were born with various morbidities. In Archangelsk Oblast and Kamchatka Krai, it was almost half.

Eight percent of the sick newborns were diagnosed with birth trauma—damage caused during the birthing process, potentially as a result of the obstetricians’ actions. In 2019 more than 35,000 children suffered birth trauma. According to Elena Berezovskaya, an obstetrician and gynaecologist and the director of the International Academy of Healthy Life, birth trauma depends on the birthing method and can be avoided in some cases.

Moscow resident Tatyana Bengraf’s daughter Olivia suffered trauma during her birth at Maternity Hospital №27 in Moscow (now the Spasokukotsky Central Clinical Hospital). Her daughter suffers from multiple illnesses as a result of the trauma: Severe damage to the central nervous system, cerebral palsy (CDC), and epilepsy.

Tatyana blames the doctors at the clinic for what happened. Other mothers who have suffered during their labour have also filed complaints about their work. Now several doctors have been suspended and the former medical director of the maternity hospital is under investigation.

‘We were expecting Olivia, of course, and went to have the ultrasound [there] and it was already obvious she looked like her dad. Everything was good, all the tests were perfect,’ says Tatyana. She says she met the doctor who was going to deliver the baby in advance. This doctor promised that the birth would go ahead without epidural anaesthetics and that if any problems cropped up, they would give Tatyana a caesarean section. But it all happened very differently. She was given multiple doses of epidural anaesthetics and oxytocin to stimulate the labour. As a result, Tatyana stopped feeling part of her body and the baby’s heart rate dropped. In Tatyana’s opinion, it was the indirect effects of the medicines that could have led to the trauma. Obstetrician and gynaecologist Elena Berezovskaya talks about the fact that each such case needs to be considered individually, but that there are situations where doctors abuse birth stimulants. ‘Sometimes they try to speed the birth up, cause births to happen when the mother’s body is not at all ready, but the doctor is impatient because their shift has finished already, or they’re going on holiday,’ she says.

The medics refused to perform a caesarean section on Tatyana Bengraf throughout the whole birth. When the baby’s heart rate started falling, the doctor and obstetrician started squeezing the infant out. ‘While they were squeezing the baby out, they completely killed her for us. When they pulled her out, her head had turned blue, meaning they had just crushed her because my hip bones were clearly not wide enough for her to push through; she was too big for my frame.’

Obstetrician and gynaecologist Elena Berezovskaya explains that this method of forcing the baby out increases the risk of birth trauma. ‘There is a directive from the Ministry of Health which prohibits forcing babies out, the Kristeller manoeuvre (although the Kristeller manoeuvre is not forcing the child out like this, it is applying pressure to the mother’s stomach, but every doctor supposedly has their own expert opinion on how to do this). And although this method is banned, it is still used in lots of maternity clinics,’ she says.

After that, according to Tatyana, her daughter was taken to the intensive care unit. ‘As a result of the fact that the neonatologists (doctors who treat newborn babies—ed. note) didn’t agree to therapeutic hypothermia (a procedure which alleviates the consequences of the trauma—ed. note), they just left her in the maternity hospital: They just put her in an incubator (a device in which premature or ill newborn babies are placed—ed. note) to die. She was lying there completely dead, just a dead baby on a ventilator with tubes and catheters. Babies were crying all around us on the ward at night; it was unbearable to hear other, healthy babies,’ Tatyana remembers.

As a result, the child developed numerous complications and spent another six months in the intensive care unit. According to Tatyana, throughout this entire time, the doctors were trying to convince her to give up on the baby: They would tell her that if she took her home, then Tatyana’s eldest daughter would see her sister and not want to have children, that her husband would leave her, that Olivia would be laying down the whole time, twitching, while her parents would ‘sit around her and just cry’. But Tatyana never once thought about giving up on her baby. Now she and her husband take it in turns to tend to Olivia around the clock, feeding her with the help of special devices. Each month the family spends around 30-40,000 Rubles on medication, another 100,000 on a specialist nanny—a healthcare worker; the state doesn’t compensate them for these costs. Tatyana finds it difficult to think about her child’s future: ‘They told us straight away that she would die. So the fact that she has already survived three years is such a great achievement for a child like her.’

Tatyana is now expecting another baby and admits that she no longer wants to give birth in Russia. ‘If the borders weren’t closed, I would fly somewhere else. Now I’ll have to think about what to do. I also wanted to fly somewhere else for the first birth because I could sense [what was going to happen]. But I stayed here, and now, of course, I regret it. Not only are they patronising and disrespectful, which, alright, you could forget about if you got the baby, and everything was okay. Not only do they treat you like this, but you end up with a crippled child, which is just horrific. All the mothers I see, many of them have only had one child, even if the child is alive and everything is okay with them, they say: ‘I’m never going back to that hell—I don’t want to give birth in this country anymore,’ Tatyana says.

‘In the interviews we conduct for our research projects women sometimes say that their first experience of giving birth was so negative and scary that they have decided to completely reject the idea of having another child and are now left with an only child,’ says Anastasia Novkunskaya, a sociologist at The European University who studies the structure of maternity services in Russia and who has talked to mothers and doctors from different regions for her research. ‘Maybe they did have a negative experience, but that doesn’t have to have such a resolute influence on their decision about future children. And it’s not always a given that the experience was that negative. This stereotype, it’s tenacious in many ways because horror stories always cause a big commotion. Cases of maternal and infant deaths are discussed a lot, and this creates a starker image than a woman talking about the fact that everything went well for her and that the doctors and obstetricians were very helpful, supportive, professional, and that she was happy and grateful for everything. These stories exist too. There are no statistics about them, but there are plenty, I think they’re even the majority.’

After Tatyana talked about what had happened on social media, other women who saw themselves as victims of the same Maternity Hospital №27 got in touch with her. As a result, the head of the maternity hospital Marina Sarmosyan and the head of the department of the pathology of pregnancy Susanna Panosyan were suspended. Now Sarmosyan is being investigated as part of a criminal case against her. The heads of each of the maternity hospital’s departments have also been dismissed. The doctors who were dismissed do not believe in the connection between the accidents and the criminal proceedings. They released an appeal in which they referred to what had happened as ‘a hostile takeover’ of the hospital. In their opinion, the dismissals were necessary to create space for doctors from another hospital that had been closed for renovations. ‘Then during the investigation, she [Panosyan] said to me: what do you want, all I got for your birth was 19,000 [Rubles]? Why does money matter? That just shows their entire attitude towards the women,’ says Tatyana, who paid 160,000 Rubles for her birth as per the contract.

‘Go and get treated and come back to us for the birth’

It’s not only the babies that suffer during labour, but the mothers too. The maternal mortality situation in Russia, according to official statistics, is getting better every year, but it is still at the same level as countries such as Saudi Arabia, Tajikistan, Turkey, and Uruguay.

Seventy-four percent of maternal deaths happen due to ‘obstetric’ reasons; the rest are due to illnesses that caused complications during the pregnancy. Obstetrician and gynaecologist Elena Berezovskaya believes that all cases of maternal mortality can be considered the responsibility of the obstetricians, seeing as though even in cases of extragenital (not directly linked to the pregnancy—ed. note) illnesses, it is doctors who specialise in these illnesses and pregnancy that are the ones observing the pregnant woman. ‘I would one hundred percent call it the obstetricians’ responsibility. This whole group could actually be lowered if the approach to understanding the women's problems was right,’ she says.

In Russia, one woman dies from complications during pregnancy or birth every two days. The majority of those who have died were being observed by doctors, and in 42% of cases, these deaths were deemed preventable. The Ministry of Health refers to such cases, for example, as death as a result of complications from anaesthetisation. ‘The Sustainable Development Agenda’ (goals the UN has set for countries to reach by 2030—ed. note) proposes ending all cases of preventable maternal deaths. Russia has not yet managed to tackle this goal.

In 36 regions of the country, the level of maternal mortality is higher than in the rest of the country. The Pskov Oblast is the worst (56.6 cases for every 100,000 mothers who give birth to live children) followed by Sakhalin Oblast (51.7) and Tula Oblast (44.5). The situation in the Pskov Oblast is comparable to the maternal mortality rate in Ecuador, in the Sakhalin Oblast to the island state of Tonga, and in the Tula Oblast to Mongolia.

Sociologist Anastasia Novkunskaya says that the regional differences could be linked to the number of maternity institutions and the availability of medical personnel. ‘If you have some kind of emergency during your pregnancy or labour and your nearest maternity clinic is not within a fifteen-minute drive, this could have a dramatic impact on how the situation develops. But even if, let’s say, you live right next to some kind of maternity department and they only have one obstetrician-gynaecologist and they don’t always work around the clock, this could also impact how fast you’ll receive emergency care.’

The maternal mortality rate is higher in Russian villages than in cities: 10.4 deaths for every 100,000 in the villages versus 8.6 in the cities. And this gap is growing every year. The causes of maternal mortality also differ in the villages and cities. For example, in the villages the most common cause of maternal death is an abortion performed outside of a medical institution—this happens almost twice as often as in the cities.

In 2017 Aram Machkalyan from Volgograd lost his newborn son and ten days after the birth his wife Elena died too. ‘My wife and I had dreams, we had big life plans. We wanted a big family. We agreed that we would even have a third child, and then we would see how life turned out,’ Aram recalls. The first time Elena gave birth in a private clinic. The second time the family decided to have the baby in a state hospital.

The pregnancy went by without any issues, but before the birth, at a New Year’s party, the woman developed a fever. When Aram called the ambulance, Elena was taken to a hospital in another city—33 kilometres away from their home. The doctors told Aram that all pregnant women who they suspected to have the flu were taken to this part of the region—to Hospital №2 in Volzhsky. After a few days in hospital, Elena suffered from uterine bleeding and was transferred to the Volzhsky Perinatal Centre. ‘The last time I checked this was why the perinatal centre existed, to deal with some kind of complications, to somehow [prevent] something from happening to the baby, to the mother—that’s what it was built for. It never occurred to me that this could happen,’ says Aram. But Elena was taken back and forth multiple times while she was ill; at the perinatal centre they told her: ‘Go and get treated and come back to us for the birth’. But when Elena went into labour, the hospital sent her back to the perinatal centre again.

Aram remembers seeing Elena for the last time: ‘They were rolling her out on a bed, she was already wearing an oxygen mask and covered with a sheet. I remember that image; it will stay with me for the rest of my life; the last time I saw her alive. I tried to give her some courage and shouted after her: “Don’t worry, we’re here, everything’s going to be okay.” In response, she looked at me—just one look.’ Just a few hours later the doctors at the perinatal centre informed Aram that his son was stillborn and that Elena had lost a lot of blood and was in a critical condition. ‘We hoped and believed, we did all kinds of things: We requested services, people of different faiths prayed in their own way. Someone offered sacrifices, someone made a donation, someone prayed. But it didn’t help, and since that moment I’ve realised I’m now an atheist. I lost my faith,’ Aram tells us.

Aram says they didn’t want to give him his child’s body: ‘It was the only thing that was important to me... He was still my son, and I still wanted him, I needed to take him away. The head doctor claimed they couldn't let me take him because he wasn’t a child, it was a foetus and they didn’t give those away. Five days later I managed to take him anyway. To bury him like a human, everything as it was supposed to be, a small grave, a little headstone, a cross.’

After his son’s funeral, Aram also lost his wife. Ten days after Elena was transferred to a new hospital, she died without ever regaining consciousness—her internal organs had failed. On the certificate that Aram was given the cause of his wife’s death was stated as autoimmune hepatitis. As Aram says, they had never given his wife that diagnosis, therefore he wrote a statement to the Investigative Committee. The forensic examination discovered that this was an incorrect diagnosis: The organs in which they had found hepatitis belonged to someone else. The pathologists had replaced the samples. Later the court found them guilty and sentenced them to nine years in prison, two of which were because of the episode with Elena. ‘Wanting to hide the real statistical data of maternal mortality in the region and prevent the negative consequences this would have for the health institutions in the Volgograd Oblast, Kolchenko and his subordinates [...] replaced the histological samples of the deceased mother with samples of the liver of another person with established chronic hepatitis,’ it says on the court’s website.

Later the two doctors from the Volzhsky Perinatal Centre who delivered Aram’s wife’s baby, Elena Popova and Natalya Andreyeva, were sentenced to two years in prison. They were convicted under the article about ‘the rendering of services which do not meet safety standards causing the death of a person through negligence’. One of the doctors’ lawyers refused to comment on the sentence in a telephone conversation with an Important Stories journalist. The lawyer of the second doctor could not be contacted. The Medical Director of the Volzhsky Perinatal Centre Alexander Bukhtin refused to comment on the actions of his staff.

‘For me, the most important thing is to remember. To remember her life, our child. They could have saved her, but they didn’t,’ says Aram. Now he is raising his six-year-old daughter alone. She has been left without a mother.

24 Hours at Work

In stories of infant and maternal deaths it’s not just those giving birth that suffer, but the doctors too, notes Anastasia Novkunskaya, a sociologist at The European University, who has gathered the opinions of doctors from various regions for her research. ‘It’s a hard job. An obstetrician's shift in a Finnish maternity hospital is eight hours maximum. So people don’t work around the clock. In Russia, it’s fairly common for a doctor and an obstetrician to be at work for 24 hours and it’s understandable that, towards the end of these full-day shifts, it is physically relatively hard to feel good and fulfil your duties.’

‘In this tired stereotype about Russian maternity hospitals being really bad, about the staff inevitably being patronising and rude to you, hurting you and so on, the medical professionals who actually work there are often looked down on,’ Novkunskaya continues. ‘One of the types of vulnerability the staff working in the field of maternity care are facing is insufficient funds: Low wages, constantly changing work rules, directives, constant inspections from control and supervisory bodies all create conditions that mean it isn’t exactly the ideal workspace. The doctors and obstetricians constantly feel these vulnerabilities: “I will now do what is right from a medical point of view, but I’ll definitely get fined, sanctioned by the control and supervisory bodies because this will contradict some sanitary rules and standards, some requirement from the Ministry of Health and so on.” This is how they have to work and what’s more, many of them really do try to do so according to professional values and some kind of humanistic ideas,’ she says.

The sociologist says that the problem could also lie in the lack of well-established communication between doctors and patients. ‘This dissatisfaction with medical care often arises not because it was really bad, but because it isn’t open enough and the communication between the doctor, the obstetrician, and the woman herself is just not smooth,’ says Novkunskaya.

A shortage of staff and ‘ageing’ medical personnel might also be having an impact on the rise in the number of infant and maternal mortalities during birth, Novkunskaya says. The statistics support her opinion: According to data from the Federal State Statistics Service, over the last few years, the availability of both maternity hospitals and obstetric beds has decreased—both for women in labour and for pregnant women with health issues, as well as the number of professional doctors. In Novkunskaya’s words, these are the effects of optimisation: Since 2015 maternity clinics have been put into conditions where they should be earning their own work, and a maternity care system is relatively expensive for medical organisations.

‘What could seriously cause some worrying issues and dangers is a decrease in the number of medical workers and medical organizations that are located far away from regional centres. Because again, the statistics show the total number of professionals, but if we look at the share of those who work in regional centres and who work on the outskirts, the proportions change. And on the outskirts, as far as I understand, access to emergency care, in particular, could decrease,’ she says.

The sociologist points out that doctors, as well as patients, are vulnerable in terms of morality. ‘Complications often arise during labour and pregnancy and the doctors will also be morally and emotionally concerned about them. Moreover, if there is a situation where the baby is lost before, during, or immediately after the birth, this is also a lot to take psychologically; it’s a source of stress for the doctors and obstetricians who are with the woman and the baby at the time. As well as a moral vulnerability we are also seeing a growth in the number of complaints and legal cases against medical organisations,’ says Novkunskaya.

Not all pregnant women die within the walls of medical institutions: 12% died outside of hospitals, and 23% did not see a doctor at all during their pregnancy (according to Ministry of Health data for 2018). Anastasia Novkunskaya says that this group might include a certain share of women from poor families who, as a result of economic factors and a lack of education, pass up on medical help. There is another group—the followers of natural childbirth, who consciously decide to have their babies at home.

According to data from the Federal State Statistics Service, around 5,000 women give birth outside of a maternity ward (this includes home births, births at the gynaecological departments of in-patient clinics, in ambulances, and in other forms of transport—ed. note). In 2020 Rostov Oblast became the stand-out leader in terms of this indicator: 372 women from this region gave birth outside a maternity hospital. This figure is twice as high as the previous year. Such an increase can be explained by the closing of maternity hospitals due to the coronavirus pandemic. As the local Ministry of Health reports, this has already managed to have an impact of the number of infant deaths in the region.

‘The rates [of infant and maternal mortality] are high in countries where there is no standard healthcare system. The conditions in which these women are living and giving birth also affect the mortality rate,’ says Elena Berezovskaya. ‘There is one more influential factor and that is socio-economic status and the development of the economy and healthcare system. Training medical staff, creating a wage for obstetricians—all of this would allow the figures to improve, i.e., increase the survival rate’.

Editor: Roman Anin