“If None of the Adults Trampled, Kids Go to School through Snowdrifts”

Why a hundred thousand Russian schoolchildren, who are due to a bus, reach school through mud and off-road — a research by IStories

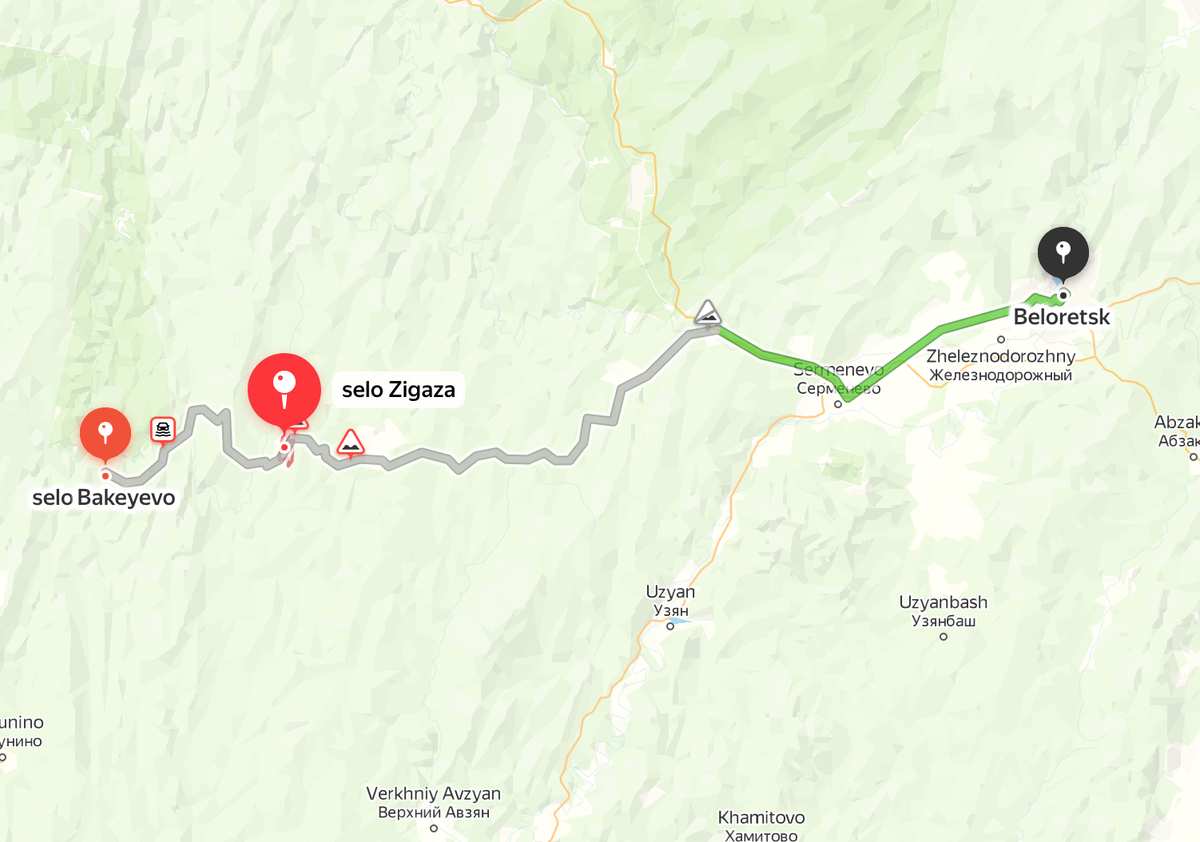

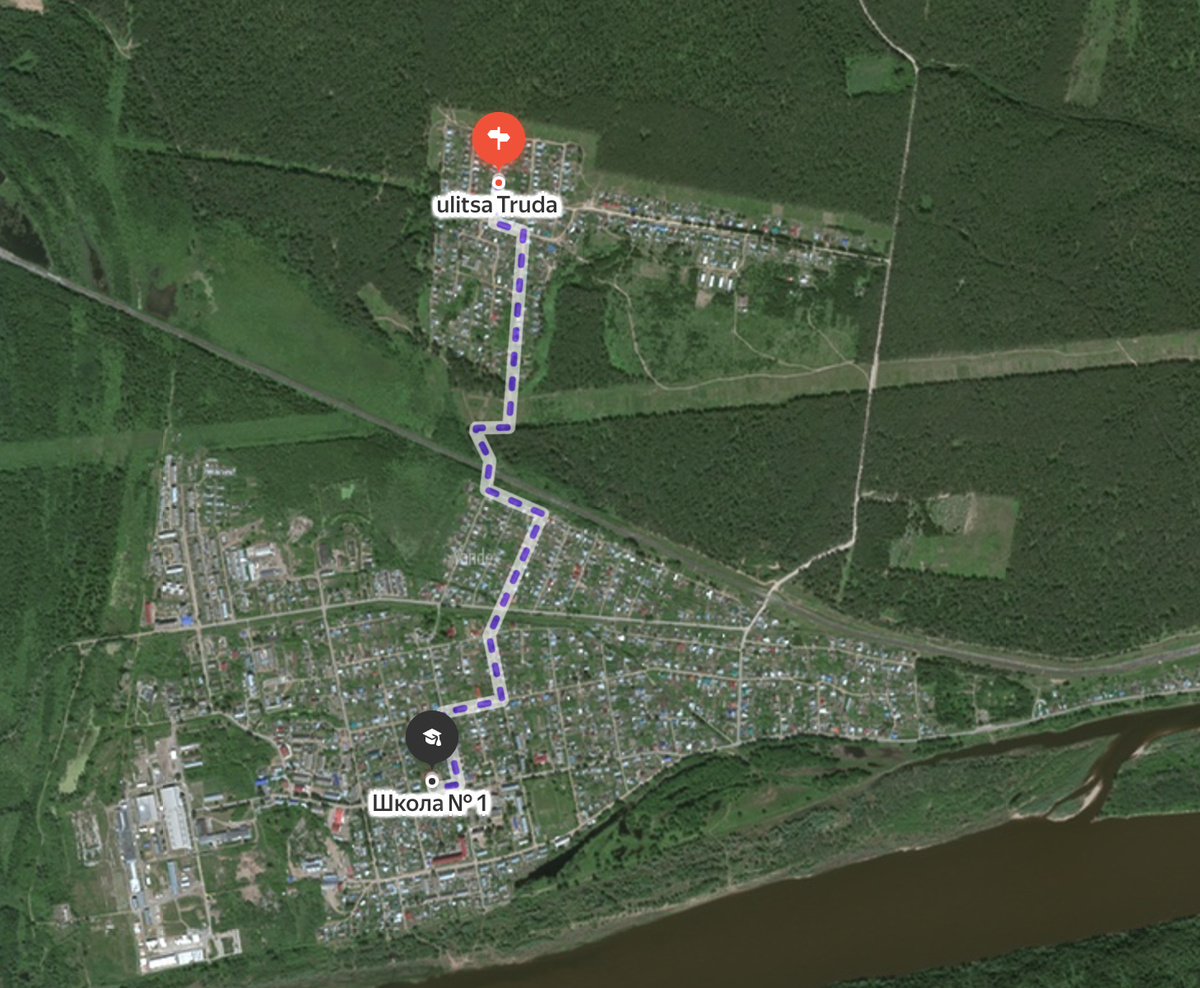

Narkas Ismagilova is a ninth grade student at a boarding lyceum in Beloretsk, the Republic of Bashkortostan. She visits her home village Bakeevo not very often. The boarding school is a forced option for all schoolchildren from Bakeevo. In 2010, the school in their village was closed for good, because only nine children remained in the village; students were transferred to the Beloretsk lyceum 115 kilometers away, 30 of which kids have to cover by themselves. Roads are very poor in the district, so the bus is unable to reach close to the village, that is why it waits for school students in the village of Zigaza – an intermediate point between Bakeevo and Beloretsk.

The road from Bakeevo to Zigaza is even worse: it can be passed only on SUVs even in summer, 30 kilometers in three hours. It becomes longer and more complicated when it rains or snows, Narkas says: “If cars break down, sometimes we get to other SUV and ride to the village on it, or just walk. We leave our belongings in the car, and the next day our dads walk there to repair the car. Parents always take two cars to have an opportunity to change if something happens. Sometimes in winter snow cleaning vehicles didn’t come when it was necessary. They came only after a fortnight and cleaned insufficiently”.

Another Bakeevo’s problem is the almost total lack of connection. When the COVID-19 pandemic began, children returned home from the boarding school. At first, teachers tried to give them home tasks via telephones, but audibility was poor, so they left this idea. Children had to move to their relatives in Beloretsk. They lived there for months.

From April to the middle of May Bakeevo becomes unreachable because of snow melting. “Rivers crossed the roads, everything including the village was flooded. People almost never come out of their homes. There is link on the hill, we went there cross the bridge before, but it broke down due to abundant water”, Narkas says. Parents cannot visit their children in the boarding school, bring them things, pay for meals; they have to borrow money from relatives.

According to “The Important Stories’” estimations, there are at least 40 localities with children residents in Russia, where schools are situated more than 50 kilometers away.

We counted the shortest straight distance from every locality in Russia to the nearest school. The information about localities was taken from ISRD (The Infrastructure of the Scientific Research Data), about schools – from the website https://schoolotzyv.ru/ (by parsing). The results were checked manually. See more in the Workshop.

Most of such villages are situated in the Murmansk, Sverdlovsk and Irkutsk regions, in the Krasnoyarsk and Trans-Baikal Territories, and Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Districts. This concerns elementary schools too.

Although, it is common when elementary schools are situated near localities, and secondary schools are far to reach. Thus, for example, in the village of Ilirney of the Chukotka Autonomous District there is an elementary school, but the nearest secondary boarding school is more than four hours away if you ride a car by a good road. Except that, calculation a distance to school does not encounter that there can be mountains, rivers, and woods on the way, which influence dramatically on the root’s length and time.

According to the sanitary standards, walking distance to school should not exceed two kilometers for elementary classes and four for secondary and senior classes. If the distance surpasses it, school students must be provided with a school bus. Still, time spent in the vehicle should not be more than 30 minutes. If a village or town is located further, or there is no satisfactory road to it, a free boarding school is due for school children.

Two and a half thousand boarding schools (meaning institutions where school students live round-the-clock) and schools at which there are boarding school departments (there are also students who reach school themselves every day in them) function in Russia. It is every twentieth educational institution of the state. In some northern regions percentage of boarding schools and schools with boarding school departments is a lot higher. E.g., the Nenets Autonomous District has only 31 educational institutions, 17 of which are boarding schools and schools with boarding school departments.

“Only a donkey can pass here, no car can ride in”

“I and my brother walk for seven kilometers from the school in the village of Gainiyamak to the village of Tukmakbash”, so the TikTok video by 23 years old Rafis Bahtiyarov is subscribed. In the video there are white fields, empty road and Rafis’s brother, 9-years-old third grader Ruslan, with a huge school bag on his back. Every Monday Rafis escorts his younger brother to school and every Friday – home.

Tukmakbash is a small village in the Republic of Bashkortostan. According to the census of 2010, its population is 55 persons. Rafis notes, that by 2021 its population reduced to 30 persons. Ruslan is the only pupil in Tukmakbash. Since late autumn to the middle of spring he stays in the boarding school in the village of Gainiyamak and comes home only for weekends. “There are no particular difficulties since spring to autumn, it becomes more difficult in winter, when freezing temperatures come. If a passing car rides, some drivers pick us up, but some pass by, and we walk”, Rafis tells us about the way to school. Rafis studied at this school too, and stayed in the boarding school for the whole week when he went to the elementary classes. When he grew up and began to go to school on his own, he returned home every day.

At the beginning of February local mass media broadcasted the story of the third grader Ruslan, and showed a new school bus, which the school had received back in December 2020, but was not allowed to use it without the Ministry of Education’s order. Than the Administration of the Alsheevsky district promised that the documents preparation will take about a fortnight, and children will be transported by bus when the papers are ready. The bus started its work only in three months. It delivered Ruslan and six other kids from remoted villages to school on May 11. But children can return home on the bus only at the end of the working week. They are supposed to stay at the boarding school during all working days, as it used to be.

The Gainiyamak school Principal Ruzilya Zakaeva told “The Important Stories” that there was no everyday delivery, because children continued to study at the boarding school: “We planned that, if there is a boarding school, the bus will bring children on Monday and return them on Friday. We hope that the boarding school will continue working next year: children from four villages remain in it, and roads are not good enough. The village of Budonyar is reachable when the weather is fine, but in winter – only if the road is cleaned”. The Principal could not answer the question if they plan to turn the delivery into daily.

The number of school students in need for buses grows every year. From 2016 to 2019, the number of school students legally dew for the transportation increased for 60 thousand persons (the Ministry of Education have not published data for 2020 and 2021 yet). In 2019, almost one million school students needed delivery, but not all of them got it: every tenth had to reach school by their own, including 44 thousand elementary school pupils.

In Tuva, Dagestan and Ingushetia more than a half of children in need for bus have to get to school by themselves. Most of the Caucasus regions have difficulties with the delivery. The leading expert of the Institute of Education of the High School of Economics Sergey Zair-Bek names two reasons for this problem: “Imagine a mountain village: only a donkey can pass here, no car can ride in. Children will have to walk all the same. And you can’t build separate schools because there are few children [in each specific village]. In addition, there [in the Caucasus regions] are more children, and more effort, resources and buses are required, and it is always complex, because the Caucasus republics always have problems with funding: they are of the poorest regions”.

In April 2021, in the message to the Federal Assembly the President Vladimir Putin promised that by 2024 16 thousand new school buses will be purchased. They could solve the problem of all children who are too far to reach school now. But it often happens that a school receives a new bus but does not use it. For instance, the school in the village of Zarubino in the Primorsky Krai fails to hire a driver for more than a year: applicants say that the salary is too low and responsibility is too high. Kids have to reach school on passing cars, and those, whose parents are afraid to let them go, stay homeschooled. But even if there is a driver, school buses often just cannot reach some locations for the reason of bad roads, as in the village of Bakeevo, where Narkas Ismagilova lives.

Even the Moscow region has difficulties: children walk from the village of Shlokhovo to the bus stop straight along the busy roadway; according to one of the locals, one kid have already been hit by a car. In answer to the requests of parents to transfer the bus stop closer to houses, the transport commission stated that there are no appropriate conditions for that.

Zair-Bek

Sergey Zair-Bek from the Institute of Education of the High School of Economics considers that, if not to apply the formal approach to the direction, it is possible to arrange delivery in the majority of cases: “Everything is about money. But recently directions of the government and the President became very important signals for regions: if the President tells to provide children’s delivery, they can forget about everything else and fund money for this. If to take local conditions into consideration, the program could be executed not in a formal way: not just to buy as many buses as the President asks, but to make all that was purchased work for increasing children’s covering with education”.

The difficulty to reach school influences children’s opportunities to get a good education; it becomes one of the factors of the educational inequality. According to the researchers of the Institute of Education of the High School of Economics, schoolchildren from rural areas get lower marks for the International program PISA than children from cities (Programme for International Student Assessment – the program of assessing educational achievements of students – Ed. note), which evaluates abilities to apply school knowledge on practice.

“There are very good village schools, fully staffed with teachers, which take into account children’s aptitudes and their further education plans”, says the Principal of the Institute of Education of NRU HSE (National Research University - Higher School of Economics - Tr. note) Irina Abankina. “And there is a plenty of such schools, especially in highly populated regions, such as the Krasnodar region, the Rostov region; in the northern regions they are in Yakutia, Komi, the Yamalo-Nenets district, on the Far East. But we have a whole section of schools which cannot provide quality education: it is about hard-to-reach areas, or understaffed schools where even the delivery is helpless. Percentage of schools with a very difficult situation is 5-6%”.

“I put three or four in the car, and others walk wet”

There are cases when uncertainties in law hamper schools to obtain a bus. These cases are not reckoned in by statistics because children are not in need of a bus according to papers, but de facto they walk to school through forest or along a highway. For instance, the village of Krasnaya Polyana in the Kirov region stretches along the river Vyatka for six kilometers. It is about 40 minutes by foot along the highway or through unlighted forest belt and railroad crossing from the community of Gora to the nearest school. “There was a school in the community before, but it was closed long ago. They promised that children wouldn’t walk on foot”, says the community resident Rustam Zhumaev. His sixth grade daughter is forced to overcome this way every day.

The bus indeed was allocated, and six years ago it had an accident. Then they found a replacement, but it carried children only till the end of the year. In 2015 school year, the school was refused to be funded for a new bus due to the Education Act. It says that free transportation of school students is made between settlements or localities. And Gora is only a community, so local schoolchildren cannot be privileged with a bus.

“There are 70 children in our community. They walk on foot for five years already, from the first grade to eleventh. All right, the weather is dry now, so they are able to reach the school. But every time it rains, I see how they are walking. I cannot put all of them in the car”, Zhumaev says. “I put three or four in the car, and others walk wet. Some return home, if they get too wet. And what about snowstorms? If an adult passed first, then there is a way. If none of the adults trampled, kids go to school through snowdrifts. Our communal services don’t perform like in Moscow from four in the morning, so people can go out to a cleaned street”.

Another danger on the way is the railroad crossing. Now it is equipped, there is a traffic light, although a simple gangway had been laying on the rails for a long time. According to Rustam, trains often stop on the crossing, and children crawl down them being afraid to be late to school.

Rustam Zhumaev attempts to solve the school bus problem for a long time. In 2019, he invited journalists from a federal TV channel to make a reportage about children from the Gora community. Other schoolchildren’s parents are dissatisfied with the way to school too, but they do not dare to fight energetically. “Everybody gives up for some reason. Maybe, they are afraid of some influence from the school. Parents are passive mostly. Even when the reporters came, I asked people to gather to emphasize that the problem concerns more than a couple of persons but the whole community. How they use to say: “What’s the point to fight?” There is a stereotype in Russia that it is worthless to fight against the system, the system will swallow you. But we are the system, us people. And people are in a sort of panic”, Rustam laments.

“Everybody gives up for some reason. Maybe, they are afraid of some influence from the school. Parents are passive mostly”.

There is a furniture factory “IKEA Vyatka” near the school, where many residents of Gora work. The corporate bus carries employees to the enterprise. Rustam came up with the idea to take advantage of this fact: “I suggested that children can be transported on the same buses. The head of the district agreed, but everything remained in words. A big bus was never ran. There is a small bus, but children wouldn’t go by it standing up together with workers. Although, if there was a big bus, both parents and children could go together”.

New students come faster than vacant places appear

The long and inconvenient way causes children to get tired, give up additional lessons, stop visiting after-classes. Rustam’s daughter in 13 now, and this year her class studies in the second shift. Due to it, she and her classmates from the remote district stopped going to basketball. In past time girls could play after school and return home with parents. “And now they are to get up early in the morning, walk to training, then back, and finally get ready and go to school. It is very hard physically. Additionally, our community is situated on the hill, so you need to go uphill. There are no roads as such, some cut and walk through the forest, and if you follow the road, there are three or four kilometers”, Zumaev says.

Study in two and sometimes even in three shifts is one more problem, which modern schools strive to cope with. “The third shift is an extremely bad situation, because it is in fact an evening education. And the second shift means that children are deprived from the opportunity to have extracurricular activities. Every standard, including the federal standard of the general education, stipulates that additional education and extracurricular activity are of its primary components. Thus, kids appear to be deprived of additional classes in frames both of extracurricular activity and additional education. And of course, it reduces their opportunities and chances in comparison to children who study in the first shift or at schools without any shifts”, explains Sergey Zair-Bek from the Institute of Education of the High School of Economics.

Studying in shifts results from schools overcrowding. And closing small schools in villages only contributes to the process. In 2015, the Ministry of Education prepared a program which supposed that by 2018 all schools will reject the third shift, and by 2021 graduate classes will study only in the first shift.

But new students enter schools faster that vacant places appear. According to the Ministry of Education, in 2020 in Buryatia, Dagestan, the Chechnya Republic and Tuva more than 18 thousand children continue studying in the third shift – only since 2016 their number doubled. Two and a half million Russian school students study in the second sift, including elementary and graduate classes.

Every year schools overcrowd primarily in big cities. In Ekaterinburg, on the night of April 1, when registration of children to first grades starts, 15 thousand parents applied simultaneously. Some schools ran out of places at once. In 2020, one Krasnodar school got 33 first grades – under the whole letters of the alphabet. There are 36 children in each class instead of the required 25.

The same is the case in Zelenograd and Odintsovo near Moscow, where the capacity of schools is almost doubled, and in many other cities. The key problem is that new communities are built rapidly and in large quantities, but new schools are not, because it is unprofitable for developers to spend money on the social objects.

In 2021, in the message to the Federal Assembly Vladimir Putin promised that 1300 new schools for more than a million school students will be built by 2024. Today, according to Rosstat, 2.1 million children study in the second and third shifts. 1300 schools will not solve the problem of the second shift, especially taking into consideration that the number of schoolchildren increase every year. Now there is 16.6 million of them, and, according to the Court of Audit, there will be 20 million by 2024. Thus, to completely reject the second shift, schools will require 4.5 million additional vacant places – excluding the million promised by the President.