“They Have Been Re-optimized to the Point That Soon No One Will Be Able to Get Sick at All”

20 million Russians may not be able to wait for an ambulance to arrive when their lives are at stake. A research and reportage by IStories

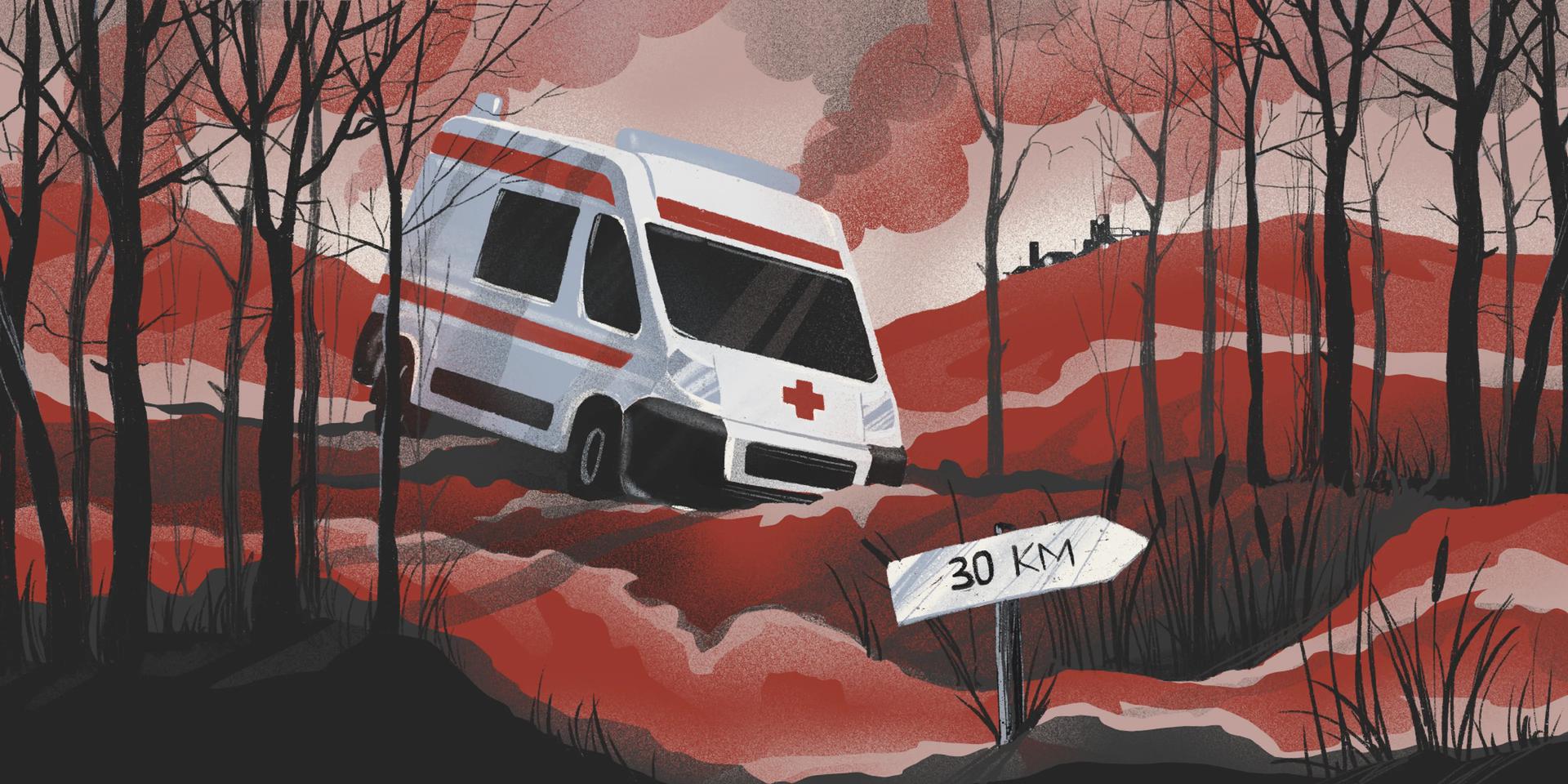

According to an order from the Russian Ministry of Health, an ambulance must reach a patient within 20 minutes if his life is in danger. "Important Stories" decided to calculate how many Russians live in settlements that are impossible for ambulance teams to reach in the time it takes to save a person. According to our calculations, 20 million people — every seventh inhabitant of Russia — will have to wait in excess of the allotted 20 minutes for the arrival of medical help. To check their calculations on the spot, iStories reporters went to a district in the Ryazan region, where the only ambulance team — three people (two paramedics and a driver) — serves 40 settlements, with a population of 10 thousand.

An ambulance team in Russia usually has a doctor, feldsher, and driver. The feldsher can be described as similar to a paramedic or physician's assistant.

"There is a three hour delay"

"Our trip was 35 minutes only one way," Lyudmila Torkhova, a medical assistant at a hospital from the village of Yelatma in the Ryazan region, announces while jumping out of the ambulance. She is met by her grandfather, a resident of the village of Stary Posad, who called an ambulance. "That wasn’t very fast ... [she] could die," he tells the paramedics and shows them the way through the garden to the house, where his wife is waiting for help — she has high blood pressure, and had a stroke in the past.

The paramedics of Yelatma hospital face similar complaints about the speed of arrival every day. In response, they can only laugh it off, “Well ... haha. What can you do?" Stary Posad, where the call originated, is located 30 kilometers from Yelatma, but is included in the service area of the Yelatma hospital. That hospital has only one ambulance left at its disposal. Its only brigade receives calls from the entire service area — in addition to Yelatma, that includes about 40 villages. Their total population together with Yelatma is more than 10 thousand people.

“There are many calls, many patients,” sighs paramedic Lyudmila Torkhova. “There is call after call, we simply do not have time to serve. There can be a delay of three hours. We have a very large service radius: seven roads depart from Yelatma, and all this is our zone. This [Stary Posad] is not even the furthest point we go to. Sometimes it takes around 45-50 minutes to get there. Now we’re here, and there [at the other end of their service zone] anything can happen. There are calls of varying complexity, and help is needed in the first minutes."

Paramedic Torkhova explains that the call from Stary Posad was non-urgent, meaning the 20 minute rule doesn’t apply, but even if it was an urgent, emergency call, the ambulance would not have been able to get there within 20 minutes: “We can’t get there faster, you can see how far the mileage is.”

“And it can happen that one call is stacked on another. Five calls will come together, but you cannot go everywhere in one vehicle at once, and that’s how it is,” ambulance driver Ivan tells Important Stories.

Local residents and ambulance workers in other localities throughout the country face the same problems seen in Yelatma. According to the calculations of "Important Stories," 20 million people — every seventh inhabitant of Russia — live in places where an ambulance from the nearest medical institution will take longer than 20 minutes to reach them. In 90 thousand settlements, there are no large medical institutions within 20 minutes' accessibility, and their residents may not be able to wait for medical assistance in the event of a life-threatening emergency. Two million of them will wait for an ambulance to arrive for more than an hour. 650 thousand people will wait for more than two hours (for more details, see the chapter "How We Counted" under the button "Check facts").

“These 20 minutes — that number doesn’t just come from nowhere — this is a certain calculation based on those critical conditions in which an increase in travel time is fraught with complications or even death,” explains Nikolai Prokhorenko, First Vice-Rector of the Higher School of Organization and Management of Healthcare.

How we counted

To assess the territorial availability of emergency medical care, we calculated the travel time from each Russian settlement to the nearest medical institution, at which an ambulance can be located. Our calculations do not take into account district hospitals and feldsher-obstetric posts (FAPs), since, according to Rosstat, most ambulance stations are located at city and central district hospitals.

To build routes, we collected the coordinates of Russian settlements and the nearest medical facilities. Data on settlements with geo-coordinates are published on the Research Data Infrastructure (INID) website. The list of medical organizations with addresses is published on the website of the Federal Compulsory Medical Insurance Fund. We geolocated their location using the Yandex Maps API.

Then we wrote a program in the Python programming language, which for each locality searches for the nearest medical facility from the list and calculates the distance to it and the time on the road — in the same way as it is displayed in Yandex maps if you build a road route from the locality to the nearest hospitals.

Since these calculations do not take into account the subdivisions of medical institutions — in particular, district hospitals and FAPs — we additionally provide data taking into account such institutions to show how many Russians do not even have access to primary care.

This data was collected from the geoinformation platform of the Ministry of Health, which for each locality shows the distance and time of delivery for the provision of medical care — it, unlike the register of medical organizations, contains data on departments. In this case, the creators of the platform consider the presence of a medical institution “within walking distance of up to an hour” as the criterion for the availability of primary care.

Russians themselves also say that they have to wait a long time for an ambulance. More than half of the respondents who called an ambulance in 2020 (54 %) waited for it longer than 20 minutes, according to the results of the "Comprehensive monitoring of living conditions of the population" survey conducted by Rosstat. Before the coronavirus epidemic, in 2018, that number was 39 %, according to a previous study by Rosstat.

According to Rosstat, most often the wait for an ambulance is delayed in the most sparsely populated rural areas (up to 200 people) and also in cities with a population of 500 thousand to 1 million: 70 % of those who called the service in 2020 waited longer than 20 minutes for it. At the same time, in villages, the average waiting time for an ambulance is 45 minutes, and in cities it’s 1 hour and 14 minutes.

The Ministry of Health does not agree with these assessments of the ambulance service’s work by Russian citizens. According to their own data, in 2020, in 83 % of cases in Russia as a whole, an ambulance reached the origin of the emergency call in less than 20 minutes. At the same time, the speed of arrival of the ambulance differs greatly by region. In 2020, the worst situation was in Kaluga region: in only 45 % of cases did an ambulance arrive in less than 20 minutes, and 22 % of residents had to wait for more than an hour. The Ryazan region was also included in the “top” three regions with the slowest ambulance services — an ambulance managed to arrive in 20 minutes only 50 % of the time there.

Before the coronavirus epidemic, ambulances arrived to calls faster, according to data from the Ministry of Health: in 2019, ambulance arrival time did not take more than 20 minutes in 89 % of cases — although in 38 regions this level was lower than the national standard: for example, in Karelia — only 69 % of calls managed to meet or undershoot the 20 minute limit. In 2020, the all-Russian mark for a 20-minute ambulance ride returned to the level of 2009-2013.

Nikolai Prokhorenko believes that the Ministry of Health data cannot be trusted, and that the truth lies somewhere in the middle between that data and the assessments of patients themselves: “Any statistical indicator that is asked for from the chief doctors or from the regional heads immediately takes on a certain political color. And, of course, failure to comply creates a certain risk situation for the head of the region. Therefore, the statistics that medical organizations submit to the top are, of course, embellished,” he says.

"Important Stories’" algorithm failed to build a route to any large hospital for 600 Russian settlements. This means that there are no roads along which it would be possible to get to medical facilities. This is also confirmed by Rosstat data — at the end of 2019, 27 % of rural settlements had no connection via hard-surface roads with the public road network.

For some Russians not only ambulances, but also primary health care is not available. According to the Ministry of Health’s geographic information platforms, in 17 thousand Russian settlements there is not at least some medical institution within an hour’s walking distance. In total, two million people live in such places. According to Nikolai Prokhorenko, residents of such centers do not go to a doctor “until the very end — [when] diseases are exacerbated and complicated."

“Someone uses their own transport, if there is one, [or] they ask their neighbors. Maybe there are even some buses [to there], but people don't even have money for them. Very often you cannot run to the hospital on the income of our villagers,” the expert adds. According to him, one of the possible ways out of the situation is to place aid points, district hospitals and FAPs as close to people as possible, “to do not as much as now, but rather twice as much.”

“How do we wait so long? With groaning and moaning”

Residents of the village of Yelatmy say that there were cases when the wait for an ambulance reached six hours. Natalia Korshunova works as a saleswoman in a Belarusian grocery store. Her elderly mother suffered a stroke — she suffers from diabetes, which is why she often needs to call the emergency service. “She urgently needed an ambulance, we waited for more than three hours. I know a case when they waited for six hours — she survived, you won't hear about it,” says Natalya.

Two months ago Natalya, along with other residents of Yelatma and villages in the district, sent a petition to the governor of the Ryazan region with a request to provide the local hospital with a second ambulance vehicle. More than 500 people signed the paper petition posted at a local pharmacy, she said.

“Before that, 15–20 minutes, and the ambulance would come to any call,” Natalya recalls when there were two ambulances in the area. “Previously, the Yelatma hospital was a separate unit, and then, due to optimization (this is the term used for the state reform of the healthcare system in Russia, which led to a reduction of hospitals and doctors – Ed.), it became a branch of the Kasimov regional hospital, and since then it has been like that. They go from call to call, and they have removed the dispatcher — it’s impossible to get through, sometimes we look for the [personal] phone number of someone from the ambulance team all over Yelatma. The doctors and paramedics are all experienced, wonderful, but what will they do? They won't do anything."

Another resident of Yelatma — her name is also Natalya — says that she recently called an ambulance, and she was told that it would arrive in three hours. “In the end I refused, I decided I’d go myself. And an old lady, a grandmother, she won’t go, or she’s disabled. I don’t know for what reason [the second] ambulance can’t be given. We have one answer to everything: 'there is no money' — all our politicians answer that way."

Yelatma’s residents are not the only ones suffering from the lack of ambulances — there are also problems for the villages included in the service area of the Yelatma hospital. “There are seven kilometers to Ermolovo via the highway, not so far for an ambulance, but we wait for an hour or two,” says Yulia Mark, a resident of Yermolov, and a pensioner. “There isn’t a big population there, about 200 people, but all are old, everyone needs the ambulance. I called a year ago, waited for the ambulance for an hour. While they drove me, I thought I would give my soul to God. They [the ambulance crew] don't even make excuses, they say: "There are no vehicles." What can it be connected with? With United Russia, with optimization. They have been re-optimized to the point that soon no one will be able to get sick at all.”

The pensioner says that until 2010 in Yermolov, there was a first-aid post with a paramedic, but now there is only a “part-time traveling nurse.” “She gets there at eight in the morning, and already at half past eleven her bus leaves. She doesn't get paid to do more. Who will sit there for five thousand [rubles] all day? There are bedridden patients, invalids that can’t walk, they have poor eyesight or hearing. Someone has to make the rounds to visit them at least once a week — this was on the paramedic’s schedule. Who will check on them now? Nobody, and they are left without help. Their wives run around, procure something, pay money to bring a doctor there. Here you are, what we have come to with this optimization."

Another village, Lasino, is located eight kilometers from Yelatma. There is also a nurse there, but, according to residents, she works around the clock because she lives there. And yet her presence in the village does not save residents from a long wait for an ambulance — “What about the nurse? She calls an ambulance and that's it. When it's half an hour, when it's an hour, and if [the vehicle] is on a call, then an hour and a half, two,” says local resident Nikolai. “How do we wait? We groan and moan."

Not only the workload, but also bad roads interfere with ambulances arriving to patients on time. “Our roads are all the same, only just this year they began to lay down asphalt,” says ambulance driver Ivan after a trip to Stary Posad. “Now one vehicle runs 300-400 kilometers per day. How will [it] work on such roads? For three years it has gone 300 thousand — how could it not break? What can we, the drivers, do but fix it ourselves. In the summer you can go everywhere, but in the spring, when there’s muddy roads, in winter it happens, there’ll be snow, you can’t go. " His words are confirmed by the ambulance’s second paramedic, Oksana Korneva: “We have a vehicle — a UAZ [light off-road military jeep], so that you can drive up anywhere. We go everywhere, and if we cannot, then we go out on foot."

“This road was built in 1987 and has not been repaired since then even once. A few times, they poured extra gravel,” says Maria, a resident of Kasimov, who in the summer moves to her parents' house in Lasino. “As soon as elections approach, we are promised manna from heaven, but we have what we have, in the end. Do you know what was here before? Life was in full swing here, all the fields were sown, there was a lot of livestock. The village was very beautiful, the places are very beautiful, we have rivers, forests with berries, mushrooms, fishing, hunting. The spots here are amazing! But everything is abandoned, complete mismanagement, the village is dying out. We have neither water nor gas. My soul asks to move here. If I live to retire, maybe I’ll move, but it’s unlikely, because there is no gas, it’s impossible to cut wood for firewood, all this costs money.”

Maria says that she herself provides medical assistance in Lasino: “Why wait? I have a medical kit with me, all first aid is here with me."

For some, the absence of a medical facility has become a reason not to seek the help of doctors at all. In 2020, every third resident of Russia did not seek help from medical organizations, although they had such a need, according to the results of the "Comprehensive monitoring of living conditions of the population" survey conducted by Rosstat.

This was mainly due to mistrust of institutions and due to the lack of free assistance: 35 % of those who did not go to doctors were not satisfied with the work of the medical establishment, 25 % could not count on effective treatment, and 16 % could receive the necessary treatment only for a fee.

Another 7 % did not seek help because it was difficult for them to get to the hospital or they could not get to it without assistance. This reason is especially common among rural residents — in 9 % of cases versus 6 % among urban residents. In the most sparsely populated areas (up to 200 people. — Ed.) this was the reason indicated by 15 % of those who did not seek medical help, despite the fact that they needed it. But even those rural residents who were able to get to the hospital often do not receive medical care due to a lack of necessary specialists — that reason was indicated by 30 % of rural residents who did not receive assistance, and 22 % of urban residents.

"It's a completely different planet - [you have to cross] a river, [take] a ferry"

Yelena Zhukova, head of the Yelatma hospital, told iStories that one ambulance was enough for them before optimization. According to her, until 2016, the hospital also had one vehicle, but the service area was smaller. “And when the organization happened, enlargement, modernization, we united [into the Kasimov interdistrict center], there were more of us, we were expanded, there were two ambulance teams,” she says, adjusting her mask, which depicts multi-colored viruses.

Since then, the paramedics of the Yelatma hospital have to go on calls to settlements 45 kilometers from Yelatma. However, this year the second ambulance broke down and the service area was not reduced. “It cannot be fixed, it [the vehicle] is so worn out, it needed to be replaced a long time ago, it ran for about eight years,” Zhukova says. According to her, now a single vehicle drives 400 kilometers per day, providing for 10-15 calls a day. “This ambulance we have came to us four years ago, and it’s already getting old, but still, compared to that [other] ambulance, it drives okay,” says the director.

Ambulance workers from different regions often talk about a shortage of vehicles, and the Ministry of Health also confirms the problem. In 2020, there were 21 thousand ambulances throughout Russia. Their number has not increased since 2013. If on average in Russia there are 15 ambulances per 100 thousand inhabitants, then in 23 regions the provision is below the all-Russian norm: for example, in the Ulyanovsk and Samara regions there are less than ten ambulances per 100 thousand people.

At the same time, only 13 % of ambulances are off-road vehicles (intended for patients in remote areas. — Ed.). According to the Ministry of Health, at least one such vehicle is missing in 33 regions. In addition, according to the Ministry of Health, all over Russia class A ambulances are rundown at a rate of 70 %, class B by 27 %, class C by 24 % (car class means the degree of equipment and crews — from the least equipped cars to transportation of class A patients, to the most equipped ‘reanimobiles’ of class C. — Ed.). “The standard service life of [most] vehicles is seven years, but de facto after five years, maybe even three, especially in rural areas, the car is trashed. But our national projects for the development of health care, which provide for the replacement of two, five, or six thousand cars, cannot even withstand planned refurbishment,” Nikolai Prokhorenko explains.

“The population is large, high mileage, left for a long time. The paramedics are trying, they eat on the road. They may get into the vehicle in the morning and return only at lunchtime,” says Elena Zhukova. “Of course, it's difficult with one vehicle. We also serve the District — it's a completely different planet: cross a river, take a ferry, then you get there, then you come back."

The district is here called the area beyond the Oka River. There are several villages on the other side of the river, which are also included in the service area of the Yelatma hospital. You can get to them only by ferry in the summer. In winter — you cross ice via hovercraft. According to local residents, in spring and autumn, during floods, it is almost impossible to get in and back out of the area.

“We have been out of contact with the mainland for six months,” says Larisa Pevtsova, a resident of the Mayak state farm in Zarechensk, as she takes reporters to the polling station, which is located in the same wooden house as the local paramedic and obstetric station (FAP). “When the ferry is running, the ambulance comes. But the ferry doesn't operate very well. I had a tragedy in 2004. We had a fire, and there [on the ferry crossing] the captain at seven o'clock in the evening made the last voyage on our side and left somewhere off on his own business, and he had to spend the night on the ferry. While they were looking for him, the house had already burned down. My husband put out the fire: he had heart problems, he shouldn’t have been carrying heavy buckets, [but] he was near the fire and died. This is the kind of medical situation where, if we had a medic, here in the Lasinsky village, the man would have been saved if he was given a timely injection. But they dragged him across the banks on the [hovercraft], they took him to Kasimov, and he gave up the ghost there."

Larisa shows a letter of gratitude issued to her by the head of the Central Election Commission (CEC) Ella Pamfilova for “successful work in holding the presidential elections” in 2018. “I think [the problems with the ambulance] are due to the fact that the local authorities spat on us, to put it bluntly. Here is the local leadership, here is the head of our Yelatma administration, so why won't they come to our meeting? I would ask how Putin is performing. Why are they discrediting United Russia? And members of "United Russia" are discrediting the authorities," said an indignant Pevtsova.

Yekaterina Simkina, 87, lives next door to Larisa in Mayak. She adds, “Our river converges, then diverges, then freezes. Nobody wants to come to us."

“Nobody needs us. She is her own doctor, she is a former paramedic. Recently, Vitka Oktyamov came [to her] with a leg,” says her daughter Galina Sysoeva, pointing at Simkina. She talks about how her mother had a seizure at twelve at night: “I had chest pains. The ambulance could not get through here — there was a flood in April, we [by ourselves] drove for an hour to the ferry, then for forty minutes we sailed upstream. An ambulance was waiting there, they took me in a state of complete exhaustion, saying: “We must go to Kasimov.” Something was not acceptable at Yelatma [hospital]. Oh, well, the [vehicle] was shaking horribly, it practically shook out my guts. If a person is about to die, he’d die on the way. We left at about half past twelve and arrived at Kasimov at three o'clock [in the morning]."

Mayak has its own FAP, but at different times it has been empty. Now three days a week for several hours a paramedic from the Yelatma ambulance service, Valery Volchenkov, a former deputy of the Yelatma settlement, works here. He says that it was his own initiative to get a job here in his spare time away from working on the ambulance team: “There was a paramedic here, but there was some kind of conflict with the local people, she left, she was offended. Then there was a guy, a local resident, he finished working before he was 27-years-old and left here, because you don't need to go to the army [Volchenkov is referring to alternative civilian service work, which allows young Russian men to avoid the country’s mandatory conscription — Ed.], you turned 27 — goodbye. Then the girl worked, got pregnant, got married, [left] for the city of Kasimov, and she works as a doctor there. And now [I] promised people that there will be a medic here — part-time, three times a week."

Yet Mayak residents say they lack round-the-clock medical care. “Why do we need this? We don’t get ill by a set schedule, I had a seizure at night. Thankfully, this person saved me”, Larisa Pevtsova says, indicating to her friend. “Well, he [the medic] probably is there, we don't know. But I think, the stairs fell off, no? The first-aid post is already useless. It is immediately clear that it is inoperative, just some kind of formalism,” adds Galina Sysoeva. According to Volchenkov himself, no one among the locals comes to him: “I work here, do you think they come to me a lot? I go from house to house, visit, ask: “How do you feel?” And they say to me: “Don't come in.” It's just the mentality of people: you need a doctor constantly, around the clock."

"After optimization, everything went downhill"

The problem with the ambulance is recognized even in the local administration. “Judge for yourself: how can you call it “emergency aid” when the visits to patients, especially in the current epidemiological situation, are in one vehicle, and the settlements farthest from our hospital are 56 kilometers in one direction and 70 in the other. [...] Please, Vladimir Vladimirovich, hear us, give Yelatma a modern ambulance,” wrote the head of the Yelatma municipality Lyudmila Anfimova, in an address that she was going to send to Putin on June 30, the day of the next Direct Line [Putin’s live yearly call-in show]. “I really believe in Putin, as a decent person,” Anfimova explains her actions, sitting in an office, next to a portrait of the president.

She says that, earlier, the Yelatma hospital was one of the best in the Ryazan region — students of the Ryazan Medical Institute came to practice with local surgeons. “After the optimization of medicine, everything went downhill. Now, instead of district hospitals, these structures have been created, which are called [IMCs] (interdistrict medical centers. — Ed.). And everyone now wants to pull as many patients as possible. One ambulance serves half of the Kasimov region. These are the opposite corners that the ambulance has to get around to — sometimes they wait for a vehicle for six hours. If it had remained our Yelatma regional hospital [so the ambulance didn’t have to serve the interdistrict center], it would have been easier for us. Optimization has led to a reduction in the number of doctors, specialists come here for only two hours from Kasimov,” says Anfimova.

“An ophthalmologist and a gynecologist come once a week, so there are long queues for them. We, if anything, immediately go to Kasimov, to paid doctors. You have to choose — you are infringing upon yourself in some way, but you go for paid services. You cannot afford everything at once, especially if you are on maternity leave. Sometimes you can't buy yourself some things, but you can go to the doctor,” says a young resident of Yelatma, Elena, walking her baby in a stroller.

Elena Zhukova, head of the Yelatma hospital, assesses the situation differently: “From narrow [specialists] there is a neurologist, a surgeon, a dentist. An ophthalmologist, a gynecologist both come, so there are no queues. The staff is older. We lack one local doctor. Some FAPs do not have enough paramedics, because the pensioners left, but the youth didn’t come. There are FAPs that are empty, that is, there are FAPs, the population is there, but there are no doctors."

According to Zhukova, the ambulance service is 100 % staffed. But one of the employees of the Yelatma hospital, on condition of anonymity, fearing dismissal, told iStories that the rest of the ambulance crews, who did not have enough vehicles, were transferred to work at the Kasimov interdistrict medical center. “We have paramedics. But in Kasimov they said this: ‘Do you want to work? Go to Kasimov. If you are not satisfied, quit your job. There are no vehicles, take your pick.’ There is no staff in Kasimov at all, everyone left, no one wants to work because of these small salaries,” she says.

Her salary is 11 thousand rubles: “What can 11 thousand rubles [per month] be enough for? Go to the store twice. Nobody comes here. Why work for such a pittance? It's a shame — you studied, you gain experience, you take responsibility. We were not given anything for the Day of the Medic [a public holiday], even if they would give a thousand [rubles], we would even be glad. Still, we work in such a dangerous situation, we get sick, we get infected."

Other employees of the Yelatma hospital also complain about the low salaries. “As an adult man, I am ashamed to talk about this. I will not talk about the salary,” replies ambulance driver Ivan.

“If in Europe at the WHO they consider about 6 % of the country's GDP to be normal spending on health care, then in our country it has [almost] never exceeded 3.2 %. From 3.5 % to 4 %, that was just last year. Therefore, the lack of funds and funding affects everything. And on the inability to maintain infrastructure, repair hospitals on time, buy equipment on time and, most importantly, pay adequate wages to health workers,” says Nikolai Prokhorenko. “Young people are less willing to go into medicine in our country. It is hard to work and study, it is extremely difficult to maintain competencies, they pay little, but responsibility increases. What kind of person, who knows all this, will go into medicine, with a sober mind?"

In recent years, the number of ambulance workers, especially doctors, has been decreasing throughout Russia. According to the Ministry of Health, in 2020, the ambulance service employed ten thousand people specializing as ambulance doctors. Compared to 2000, their number has decreased by half. The proportion of the population with access to ambulance doctors decreased by 40 % over the same period — if in 2000 there were 12 doctors per 100 thousand people, then in 2020 there were only seven doctors.

Since 2008, the number of doctors in 57 regions of Russia has more than halved. The Ulyanovsk region became the “leader” in this reduction — the number of doctors in the region decreased by six times compared to 2008.

If throughout the whole of Russia there are seven doctors specializing in emergency medical services per 100 thousand people, then in 49 regions the number is less than the national average. In the Kaluga, Ulyanovsk, Kurgan, Bryansk and Chelyabinsk regions, Karachay-Cherkessia and the Jewish Autonomous Region, there are only two ambulance doctors per 100 thousand people.

Judging by data from the Ministry of Health, ambulance teams (with a doctor) are being replaced by paramedics — over the past 18 years, the number of specialized teams has decreased by 19 % and 30 %, respectively, while the number of paramedic teams has increased by 61 %. Nikolay Prokhorenko says that replacing medical teams that have a doctor with paramedic teams is a reflection of the general shortage of doctors, and this is a negative trend for a country with poor accessibility of medical care: "Since it is often difficult to get there, the importance of providing adequate qualified assistance on the spot is of great importance," he says.

However, there is a shortage of ambulance personnel among all positions — in 2020, 31 % of ambulance positions and 11 % of positions for paramedical personnel were not occupied. These figures are worse than in 2010, when the shortage of doctors on ambulances was 14 %. For nurses the number was only 3%.

The decline in health care resources has not only affected the ambulance service. In Russia as a whole, from 2000 to 2020, the number of hospital beds decreased by 35 % — from 1.6 million beds to 1 million beds. This also influenced a 27 % reduction in the provision of beds for the population: in 2000, there were 116 beds per 10 thousand people, and in 2020 there were just 70 beds. Rural settlements have suffered the most. The number of beds in rural areas has decreased by 40 % over the past 20 years — the provision of beds based on population has decreased by 36 %.

During the same time period, the number of doctors in Russia decreased by 8 %, and the number of paramedical personnel by 14 %. If before there were 48 doctors per 10 thousand people, then in 2020 the number was 38. The availability of doctors has decreased by 19 %. The pool of paramedical personnel decreased by 26 %.

This happened not only due to job cuts, but also due to a lack of specialists. If in 2000 Russia needed to fill 6 % of necessary doctor positions, then in 2020 it is 19 %, according to the Ministry of Health. As for the nursing staff, in 2000 4 % of positions were open, and in 2020 the number is 11 %.

At the same time, the provision of rural residents with doctors increased, but there were fewer nurses in villages. Thus, the number of nurses working in paramedic and paramedic-obstetric points has decreased by 41 % since 2005, including feldshers — by 30 %.

"Well, excuse me, we do have norms"

“Over the past ten years, the availability of medical care has significantly decreased,” says Nikolai Prokhorenko. “But we must not forget that somewhere over the past ten years, the incidence has been growing by 3.6 % per year. Therefore, the norms of ten years ago cannot be compared with the provision now. The incidence rate has increased by 35–36 %, so the current need for medical care must be taken into account, but it was recalculated for the last time at the turn of the 70s–80s, of the last century. With the money allocated for all this, it is impossible to provide necessary medical care.”

The Yelatma administration also explains that the impossibility of providing a second ambulance is due to a reduction in healthcare costs, which is regulated at the federal level. “The fact that there is only one vehicle, well, excuse me, we have norms that are not calculated here, they are calculated at the federal level. We are forced to live by these standards. We are modernizing medicine, which also affected emergency medical care. Modernization is about reducing costs. There are some calculation norms by which they are guided, and these norms show that we should have one ambulance for our outfit. I have no right to interfere in their calculations,” says the head of the village of Yelatma, Grigory Danilov. “The word ‘optimization’ is, in principle, not bad, just recently it turns out that not everything that is being optimized works as it was originally intended.”

Danilov says that he himself is in favor of providing Yelatma with a second and even a third ambulance, but it is impossible to allocate money for this from the local budget. “We do not distribute health care. This money is not in the local budget, all this distribution starts from the regional level, from the federation,” he says.

The Minister of Health of the Ryazan region, Andrei Prilutsky, did not see a problem with the fact that there was only one ambulance left in Yelatma. When questioned by "Important Stories," he replied that the Russian Ministry of Health, in an order from 2018, recommends a standard of one ambulance brigade per ten thousand population. According to him, in Yelatma, where the population together with the nearest settlements is 10,712 people, this standard is being fulfilled.

“There are people who are following the issue closely, and, for example, a chief physician with a lot of experience, with undisturbed honor and conscience will not stop at the level of regional minister. He will go to the governor, go to the director of a large plant, beg for a vehicle and other things that will allow him to fulfill this state standard. It turns out that these associates will do this in spite of the situation that exists, because we have very, very little money for fulfilling the standards, it is not enough,” Nikolai Prokhorenko believes. “The region has the right to add an ambulance, but there is no money for that. But surely there are stupid cost directives that could be dispensed with. And here the question is in the choice of priorities. If the governor believes that the provision of medical care for the people is extremely important, he, God knows, will find funds — it isn’t that much for additional vehicles. If we call ourselves a social country, a developed country, then we must ensure all this.”